Biological immortality remains impossible due to fundamental limits in human biology. The Hayflick limit restricts normal body cells to about 50-70 divisions before they enter replicative senescence and stop dividing, acting as a built-in molecular clock. This is driven by telomere shortening—protective caps on chromosomes that erode with each cell division because of the end replication problem. When telomeres get too short, cells trigger senescence or programmed cell death to avoid instability. Accumulated DNA damage, oxidative stress from metabolism, declining mitochondrial function, and rising entropy further accelerate aging, leading to protein aggregates, tissue dysfunction, and brain decay. Cancer cells bypass these barriers through telomerase activation for indefinite growth, but this causes tumors rather than healthy longevity. While anti-aging research explores ways to slow telomere loss, clear damaged cells, or reduce oxidative stress, no approach can fully overcome these intertwined mechanisms. True indefinite lifespan without disease or decline is currently beyond scientific reach.

Long Version

The Scientific Barriers to Biological Immortality: Why True Longevity Remains Elusive

In the quest for immortality, humans have long dreamed of defying aging and achieving biological immortality—a state where the body could theoretically live indefinitely without succumbing to senescence. Yet, despite advances in science, this remains impossible due to fundamental biological processes like the Hayflick limit, telomere depletion, accumulated DNA damage, entropy, and brain decay. These mechanisms ensure that cell division eventually halts, leading to physical collapse. This article explores these barriers in depth, drawing on established research to provide a clear understanding of why longevity has limits and what it means for anti-aging therapeutics.

The Hayflick Limit: A Cellular Countdown to Senescence

At the heart of aging lies the Hayflick limit, discovered in the 1960s. This phenomenon describes the finite number of times somatic cells can divide—typically around 50 to 70 times—before they enter replicative senescence, a state where they stop proliferating and become dysfunctional. This replicative lifespan acts as a molecular clock, ticking down with each cell division due to the end replication problem, where DNA polymerases fail to fully copy the ends of chromosomes. As cells approach this limit, they accumulate damage, contributing to overall tissue decline and reducing the potential for cellular immortality.

Replicative senescence serves as a protective mechanism against uncontrolled growth, but it also accelerates aging. In contrast, certain cells like stem cells maintain some regenerative capacity, yet even they are not exempt from eventual exhaustion. This limit underscores why biological immortality is unattainable: without infinite cell renewal, organs and systems inevitably falter. To enhance our understanding, consider that environmental factors, such as radiation or toxins, can accelerate reaching this limit, further emphasizing the role of external stressors in curtailing cellular potential.

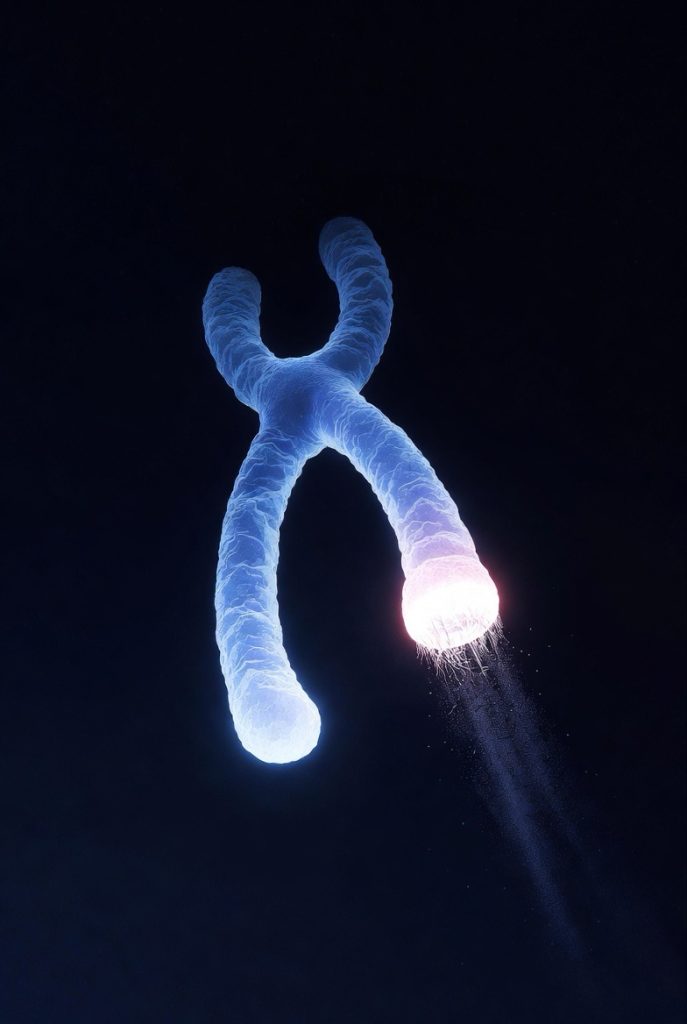

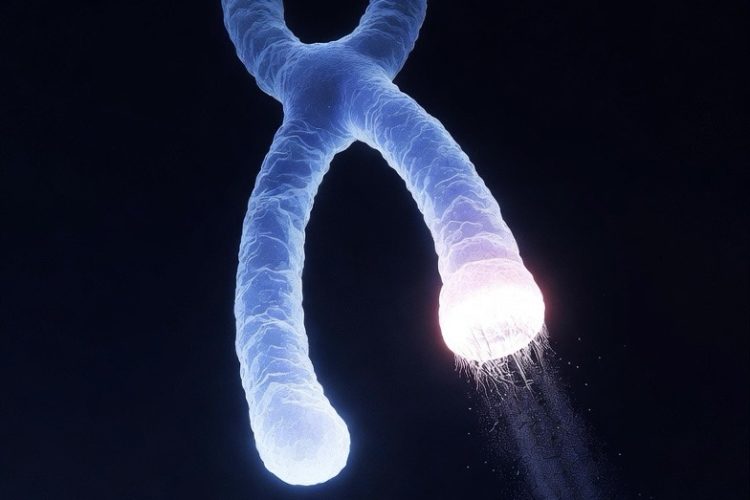

Telomeres: The Protective Caps That Erode Over Time

Telomeres, often called chromosomal caps, are repetitive DNA sequences at the ends of chromosomes that protect against chromosomal instability. With each cell division, telomere shortening occurs because of the end replication problem, leading to telomere erosion. When telomeres become critically short, cells trigger senescence or programmed cell death to prevent genomic chaos.

Telomerase, an enzyme that adds DNA to telomeres, is active in germ cells and some stem cells but largely absent in somatic cells, limiting their replicative potential. In cancer cells, however, telomerase reactivation enables cellular immortality, allowing indefinite division—but at the cost of tumor formation. This double-edged sword highlights a key challenge: extending telomeres might enhance longevity but risks chromosomal instability and malignancy. Enhancing this section, it’s worth noting that lifestyle factors like exercise and diet can modestly slow telomere shortening, offering practical ways to influence aging at a cellular level, though not enough to achieve immortality.

DNA Damage and the Quest for Genome Stability

Aging is marked by mounting DNA damage from environmental factors, replication errors, and internal stressors, compromising genome stability. Over time, this damage accumulates, impairing cell function and leading to mutations that can either cause cell death or, paradoxically, fuel diseases like cancer.

Programmed cell death, or apoptosis, eliminates damaged cells, but as repair mechanisms weaken, survivors contribute to tissue dysfunction. Stem cells, vital for regeneration, also suffer from this instability, reducing their ability to replenish tissues. HeLa cells, derived from cervical cancer and immortalized through telomerase activity, exemplify how bypassing these safeguards leads to uncontrolled growth rather than healthy longevity. To deepen the insight, DNA repair pathways, such as base excision repair and non-homologous end joining, become less efficient with age, creating a compounding effect that makes comprehensive genome maintenance increasingly challenging.

Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction: The Energy Crisis of Aging

Oxidative stress arises from reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced during cellular metabolism, damaging proteins, lipids, and DNA. Mitochondria, the cell’s powerhouses, are particularly vulnerable; impaired mitochondrial function reduces energy production and amplifies ROS, creating a vicious cycle that hastens senescence.

As mitochondrial function declines, cells struggle to maintain homeostasis, leading to protein aggregates—misfolded proteins that clump and disrupt function, as seen in neurodegenerative diseases. This interplay between oxidative stress and mitochondrial decline is a core driver of aging, making biological immortality improbable without revolutionary interventions. For enhancement, antioxidants from diet, such as vitamins C and E, can mitigate some oxidative damage, but they fall short of reversing the underlying mitochondrial wear and tear that accumulates over decades.

Entropy and Brain Decay: The Inevitable Disorder

From a thermodynamic perspective, entropy—the tendency toward disorder—increases in biological systems over time, manifesting as accumulated damage that repair processes can’t fully counteract. In the brain, this leads to brain decay, where neurons lose efficiency, synapses weaken, and cognitive decline sets in.

Unlike other tissues, the brain has limited regenerative capacity, with stem cells playing a minor role in repair. Protein aggregates in the brain, such as those in Alzheimer’s, exemplify how entropy exacerbates decay, rendering immortality unfeasible as neural integrity erodes. Enhancing this, emerging research into neuroplasticity shows that mental stimulation and physical activity can build cognitive reserves, delaying decay, but entropy’s inexorable rise ensures that complete prevention remains out of reach.

Lessons from Immortal Cells: Cancer, HeLa, and Beyond

Cancer cells achieve a form of cellular immortality by evading senescence through telomerase activation and ignoring DNA damage signals. HeLa cells, the first immortal human cell line, demonstrate this: they divide indefinitely but are cancerous, not a model for healthy immortality.

This reveals a trade-off: mechanisms enabling immortality in cells often promote disease, as seen in how cancer exploits programmed cell death pathways for survival. Stem cells offer hope for regeneration but face the same limits of telomere erosion and oxidative stress. To expand, studying these cells has led to breakthroughs in regenerative medicine, like induced pluripotent stem cells, which hold promise for tissue repair but still grapple with the same fundamental barriers to indefinite lifespan.

Anti-Aging Therapeutics: Progress Amid Challenges

Anti-aging therapeutics aim to extend longevity by targeting these barriers, such as boosting telomerase or clearing senescent cells. Compounds like those activating glycolysis pathways show promise in mitigating oxidative stress and protein aggregates. However, challenges persist: enhancing genome stability without risking cancer, or improving mitochondrial function without side effects.

Recent advances, including CRISPR-edited cells and exosomal therapies, suggest ways to rejuvenate tissues, but they don’t eliminate entropy or the Hayflick limit entirely. True biological immortality would require overcoming all these hurdles simultaneously, a feat beyond current science. For enhancement, ongoing clinical trials in senolytics—drugs that remove senescent cells—illustrate tangible progress, potentially adding healthy years to life, though not indefinitely.

Conclusion: Embracing the Limits of Life

Biological immortality eludes us because of intertwined processes like the Hayflick limit, telomere shortening, DNA damage, oxidative stress, protein aggregates, mitochondrial function decline, entropy, and brain decay. While anti-aging therapeutics offer incremental gains in longevity, they can’t rewrite the fundamental rules of senescence and cell division. Understanding these barriers fosters appreciation for life’s finite nature and drives ethical, evidence-based pursuits in aging research. As science progresses, we may extend healthy years, but absolute immortality remains a scientific impossibility—for now.