San Francisco’s groundbreaking 2025 lawsuit against major food giants like PepsiCo, Coca-Cola, Kraft Heinz, and General Mills accuses them of fueling a public health crisis by engineering ultra-processed foods that are deliberately addictive and linked to rising rates of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, cancer, and mental health issues. Using the NOVA classification, these hyper-palatable products—loaded with sugars, fats, salts, and additives—are designed to trigger cravings while displacing nutrient-rich whole foods from everyday diets. The case highlights deceptive marketing tactics targeting children and vulnerable communities, drawing parallels to Big Tobacco, and seeks accountability for massive healthcare costs. As awareness grows, consumers can take control by reading labels, prioritizing fresh and minimally processed options, and making simple swaps to reduce reliance on these convenient but potentially harmful snacks, paving the way for healthier habits and possible industry-wide reforms.

Long Version

Exposed: San Francisco’s War on Ultra-Processed Foods – Are Your Snacks Killing You?

In a move that’s igniting debates across dinner tables and boardrooms alike, San Francisco has taken a stand against the pervasive influence of ultra-processed foods in our daily lives. On December 2, 2025, City Attorney David Chiu filed a pioneering lawsuit in San Francisco Superior Court, targeting 10 major food manufacturers for allegedly creating a public health crisis through deceptive practices. This action accuses household names behind everything from sodas to snack packs of engineering products that are not only convenient but potentially addictive and detrimental to health. With chronic diseases on the rise and healthcare costs soaring, the case prompts us to question: Are the quick bites we grab on the go quietly eroding our well-being?

This lawsuit arrives at a pivotal moment, as awareness grows about how ultra-processed foods dominate modern diets, accounting for roughly 60% of caloric intake in the U.S. and contributing to epidemics of obesity, diabetes, and more. Drawing inspiration from past battles against industries like tobacco, it seeks accountability for what plaintiffs describe as deliberate harm. In this comprehensive guide, we’ll dissect the essentials—from defining ultra-processed foods and their health implications to the lawsuit’s details, practical avoidance strategies, and broader societal shifts. Whether you’re a busy parent, health enthusiast, or curious consumer, arming yourself with this knowledge can empower smarter choices in a landscape filled with tempting options.

Defining Ultra-Processed Foods: Beyond the Label

To grasp the controversy, start with the basics: What are ultra-processed foods? These items go far beyond simple preservation techniques. According to the widely adopted NOVA classification system developed by researchers at the University of Sao Paulo, ultra-processed foods are industrial creations made from substances extracted from foods, combined with additives like flavors, colors, emulsifiers, and preservatives. They’re designed for long shelf life, hyper-palatable taste, and mass appeal, often at the cost of nutritional integrity.

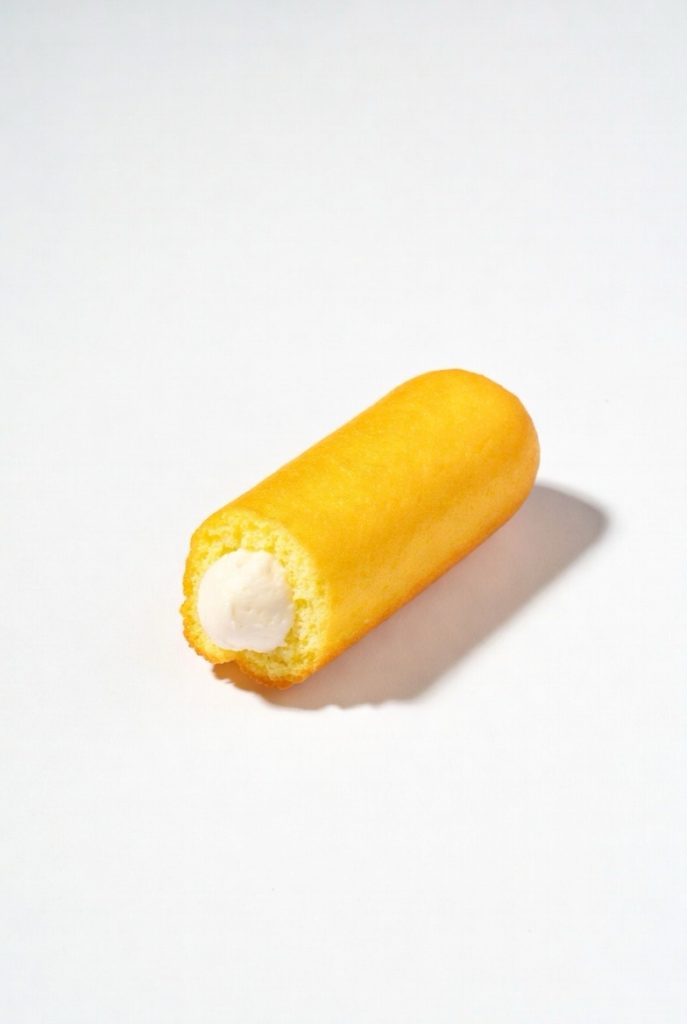

Examples of ultra-processed foods abound in grocery aisles: sugary sodas from PepsiCo or Coca-Cola, packaged cereals like those from General Mills or Kellogg, candy bars from Mars, crackers from Mondelez, frozen meals from ConAgra Brands, and processed meats from Post Holdings or Kraft Heinz. Nestle USA’s contributions include items like instant noodles and sweetened yogurts. These aren’t just treats; they’re engineered with precise formulations—think the perfect crunch of chips or the irresistible fizz of cola—to encourage repeated consumption.

What sets them apart from processed foods? The latter might include basics like canned beans or yogurt, which undergo minimal changes to make them safe and accessible. Ultra-processed versions, however, incorporate ingredients rarely used in home cooking, such as high-fructose corn syrup, hydrogenated oils, or artificial sweeteners. This industrial process often diminishes fiber, vitamins, and minerals while amplifying calories from sugars and fats.

The rise of these products traces back to the 1970s and 1980s, when industry consolidation allowed a handful of corporations to control about 70% of the U.S. food supply. Economic pressures favored cheap, scalable production, leading to a flood of affordable, addictive snacks. Globally, similar patterns emerge in countries like Brazil and the UK, where ultra-processed foods now comprise over half of diets, correlating with rising health issues. Yet, in places with strong regulations, like France’s Nutri-Score labeling, consumption has dipped, hinting at potential solutions.

The San Francisco Lawsuit Against Food Giants: Unpacking the Claims

At the core of San Francisco’s ultra-processed foods lawsuit is a charge of systemic deception. Filed on behalf of California residents, the complaint alleges violations of the state’s Unfair Competition Law and public nuisance statutes. The 10 defendants—Kraft Heinz Company, Mondelez International, Post Holdings, The Coca-Cola Company, PepsiCo, General Mills, Nestle USA, Kellogg, Mars Incorporated, and ConAgra Brands—are accused of knowingly designing and marketing harmful products while concealing risks.

Key allegations paint a picture of calculated strategy: These companies allegedly engineered addictive snacks using “bliss point” science to optimize sugar, fat, and salt ratios, triggering brain responses akin to those from nicotine or opioids. Marketing tactics reportedly target vulnerable groups, including children through colorful packaging and cartoons, and low-income communities with aggressive advertising in areas lacking fresh food access. The suit references a 1999 industry meeting where executives acknowledged addiction potential but proceeded anyway, prioritizing profits over public health.

Parallels to Big Tobacco are explicit, with claims that big food companies suppressed research, funded biased studies, and lobbied against regulations. San Francisco points to skyrocketing healthcare burdens: In 2024, the city spent millions on diet-related illnesses through programs like Medi-Cal, with diabetes hospitalizations alone costing over $85 million in recent years. Statewide, chronic diseases linked to poor diets drain billions annually.

As of early 2026, the case remains in preliminary phases, with defendants arguing that personal choice and lack of a standardized UPF definition undermine the claims. Industry representatives emphasize that their products meet FDA safety standards and provide affordable nutrition in a fast-paced world. Previous private suits, like the 2024 Martinez case against similar defendants, faced dismissals for insufficient specificity, but this government-backed effort could fare differently due to its public nuisance framing.

Counterarguments deserve attention: Not all experts agree on UPF causation, noting that correlation doesn’t prove direct harm, and factors like sedentary lifestyles contribute to health woes. Some defend processing for enabling food security in underserved regions. Nonetheless, mounting evidence from international bodies like the World Health Organization supports the lawsuit’s premise, urging reduced UPF intake globally.

Health Impacts Explored: How Do Ultra-Processed Foods Affect Health?

Why are ultra-processed foods bad? The science reveals a web of interconnected risks, affecting everything from metabolism to mental well-being. Diets heavy in UPFs are linked to a 21% higher mortality risk, per large-scale reviews involving millions of participants.

Metabolically, these foods disrupt balance: High in refined carbs and sugars, they cause rapid blood sugar spikes, fostering insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Excessive sodium contributes to hypertension and heart disease, while trans fats and additives promote inflammation, elevating cardiovascular risks. Cancer connections are notable, with studies associating UPFs to increased incidences of colorectal and other diet-related malignancies, possibly through gut microbiome alterations or carcinogen formation during processing.

On addiction: Food addiction isn’t mere willpower failure; neuroimaging shows UPFs activate reward centers similarly to substances, leading to cravings and overconsumption. A controlled trial had participants on UPF diets unwittingly eating 500 extra calories daily, resulting in weight gain and fat accumulation.

Mental health ties are emerging: Nutrient deficiencies from displacing whole foods correlate with higher depression and anxiety rates, as essential omega-3s and antioxidants are scarce. For children, early UPF exposure heightens risks of obesity, fatty liver disease, and behavioral issues, with long-term consequences like reduced life expectancy.

Nuances exist: In moderation, UPFs might not harm everyone equally—genetics, activity levels, and overall diet play roles. Some fortified UPFs address deficiencies in specific populations, like vitamin-enriched cereals in low-income areas. However, consensus from bodies like the American Heart Association recommends capping UPFs at 10-20% of calories, favoring whole foods for sustained health.

Global angles add depth: In low- and middle-income countries, UPF influx via trade agreements has spiked obesity rates, prompting policies like Mexico’s front-of-pack warnings, which reduced purchases by 10%. These insights underscore that while individual choices matter, systemic changes are crucial.

Practical Strategies: How to Avoid Ultra-Processed Foods Effectively

Transitioning away from ultra-processed foods needn’t be drastic; thoughtful swaps yield big benefits. Begin with awareness: Scan labels for lengthy ingredient lists or unfamiliar additives—aim for recognizable components.

Shopping smarter: Prioritize perimeter aisles for fresh produce, meats, and dairy, minimizing inner-aisle temptations. Choose minimally processed alternatives, like plain oats over flavored cereals or fresh fruit over fruit-flavored snacks.

Meal prep empowers control: Dedicate time to batch-cooking whole-food meals, such as veggie stir-fries, salads with nuts, or homemade soups. For on-the-go needs, prepare trail mixes or veggie sticks with hummus.

Addressing cravings: Combat food addiction by incorporating satisfying fats and proteins—avocados, eggs, or beans—to stabilize blood sugar. Hydrate with water or herbal teas instead of sodas, and experiment with herbs and spices for flavor without additives.

Family-friendly tips: Engage kids in cooking to build healthy habits; turn it into games, like identifying “real food” at stores. For budgets, leverage seasonal produce, bulk grains, and community gardens.

Longer-term: Track progress with apps monitoring UPF intake, and advocate for change through supporting local policies or choosing brands reformulating products. Research indicates that reducing UPFs by even 25% can lower disease risks substantially, improving energy and mood.

Challenges include time constraints and accessibility, particularly in food deserts. Solutions? Community programs, like urban farming initiatives, bridge gaps, ensuring inclusivity across socioeconomic lines.

Broader Implications: Toward a Food Industry Revolution

This lawsuit could catalyze transformative shifts. Success might compel reforms: Enhanced labeling, marketing restrictions on kids’ products, or even product redesigns to reduce addictiveness. Economically, it could redistribute costs, with penalties funding health programs, potentially saving billions in medical expenses.

Industry responses vary: Some companies are pivoting to healthier lines, like reduced-sugar sodas or plant-based snacks, driven by consumer demand. Trends show millennials and Gen Z favoring clean-label brands, boosting markets for organic and minimally processed goods.

Globally, precedents like Chile’s black octagon warnings have curbed UPF sales, inspiring U.S. adaptations. Ethical considerations loom: Balancing corporate innovation with public welfare requires nuanced regulation, avoiding overreach that stifles food diversity.

Counterviews warn of unintended consequences, like higher prices hitting low-income families or stifled innovation. Yet, the momentum toward transparency aligns with broader wellness movements, including federal initiatives like Make America Healthy Again.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Control in the Ultra-Processed Era

San Francisco’s bold challenge to ultra-processed foods illuminates a critical crossroads for public health and industry accountability. We’ve explored their definitions, health tolls, the lawsuit’s intricacies, avoidance tactics, and far-reaching effects, revealing a landscape where informed choices intersect with systemic reform.

Empowerment lies in action: By questioning what’s in your cart and embracing whole foods, you contribute to personal vitality and collective change. As this story evolves, remember—health isn’t just about avoidance but building sustainable habits in a world of choices. Stay vigilant, eat intentionally, and champion a future where food nourishes rather than undermines.