Cracking your knuckles doesn’t cause arthritis, a common myth debunked by science. The popping sound comes from gas bubbles (mostly nitrogen) in the synovial fluid bursting in the joint capsule when you stretch the metacarpophalangeal joints—a process called tribonucleation. Studies, including long-term research on habitual knuckle crackers, show no link to osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis, with similar arthritis rates in crackers and non-crackers. One famous self-experiment over 60 years found no difference between cracked and uncracked hands. However, frequent cracking may lead to minor issues like hand swelling, reduced grip strength, or rare ligament strain. It provides temporary relief and feels satisfying for many, but if it hurts, stop. Overall, knuckle cracking is generally harmless for joint health, so you can continue without worrying about arthritis.

Long Version

Debunking the Myth: Does Knuckle Cracking Really Cause Arthritis?

For generations, the familiar popping sound of knuckle cracking has sparked debates and warnings from concerned parents and friends alike. Many believe this common cracking habit leads to arthritis, joint damage, or long-term wear and tear on the hands. But is there truth to this notion, or is it just another health myth debunked by science? In this article, we’ll explore the mechanics behind knuckle cracking, examine the evidence from studies on habitual knuckle crackers, and address potential risks to hand health, including grip strength and functional hand impairment. Drawing on reliable medical research up to 2025, we’ll provide a clear, evidence-based answer while distinguishing between types of arthritis like osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.

The Science of the Pop: What Happens When You Crack Your Knuckles

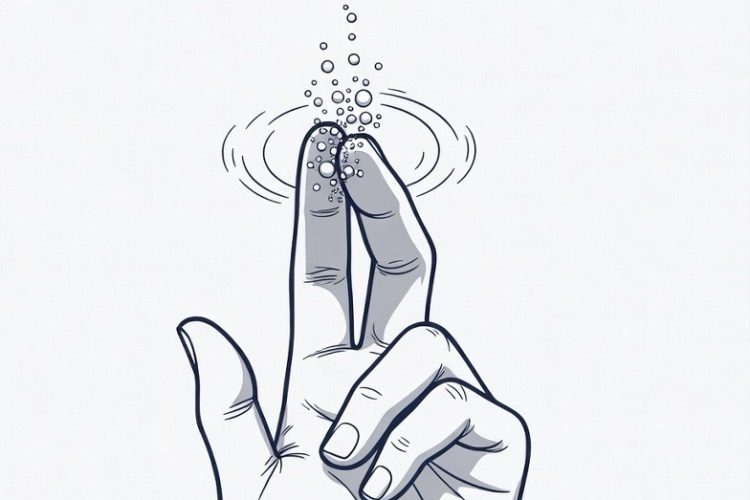

Knuckle cracking occurs at the metacarpophalangeal joints, the finger joints where the hand bones meet the fingers. These joints are enclosed in a joint capsule filled with synovial fluid, a thick, lubricating substance that nourishes the cartilage and reduces friction during movement. Dissolved within this synovial fluid are gases, primarily nitrogen bubbles and other gas bubbles like carbon dioxide.

When you pull or bend your fingers to crack your knuckles, you’re stretching the joint capsule. This action creates a sudden drop in pressure inside the joint, forming a vacuum. The process, known as tribonucleation, causes the dissolved gases to come out of solution and form a bubble—essentially, an adhesive seal breaks as the fluid cavitates. The resulting popping sound, often described as crepitus in medical terms, is the bubble’s formation or collapse. Recent studies using real-time imaging have confirmed that the sound stems from this cavity inception in the synovial fluid rather than any bone-on-bone contact. It takes about 20 to 30 minutes for the gases to redissolve, which is why you can’t immediately re-crack the same knuckle.

This mechanism explains why knuckle cracking feels relieving—joints temporarily feel looser with improved mobility. However, it’s not without debate; some research suggests the vibratory energy from the pop could theoretically mimic forces that cause wear and tear in other contexts, like industrial machinery, but human joints appear resilient to this. Enhanced understanding from biomechanical models in recent years further supports that the forces involved are well within the joint’s tolerance, preventing any cumulative damage from typical cracking.

The Arthritis Connection: Examining the Evidence

The central question—can knuckle cracking lead to arthritis?—has been thoroughly investigated, and the consensus is clear: no, it does not. Arthritis encompasses various conditions, including degenerative arthritis (osteoarthritis), where cartilage breaks down over time due to wear and tear, and inflammatory arthritides like rheumatoid arthritis, driven by autoimmune responses. Neither type has been linked to knuckle cracking in scientific studies, with reviews as recent as 2025 reaffirming this position.

One of the most cited pieces of evidence comes from a decades-long self-experiment where a researcher cracked the knuckles on one hand at least twice daily for over 60 years while leaving the other untouched. Imaging later showed no difference between the hands and no signs of arthritis in the cracked one. The conclusion: There is no apparent relationship between knuckle cracking and the subsequent development of arthritis of the fingers.

Larger studies support this. A retrospective analysis of 215 people aged 50 to 89 found that 20% were habitual knuckle crackers, but the prevalence of hand osteoarthritis was similar between crackers (18.1%) and non-crackers (21.5%). Even when broken down by joint type, including metacarpophalangeal joints, no correlation emerged. Total duration and frequency of cracking also showed no link to osteoarthritis. Another study of 300 patients echoed this, finding no increased arthritis risk, though it noted other effects we’ll discuss later.

Medical institutions affirm there’s no evidence associating knuckle cracking with arthritis. In fact, some research even suggests an inverse correlation in certain joints, meaning crackers might have slightly lower osteoarthritis rates, though this isn’t causative. Hand surgeons emphasize that knuckle crackers maintain the same range of motion and function as non-crackers, with no arthritis development. Longitudinal studies and clinical evaluations through 2025 consistently indicate that habitual knuckle cracking does not increase the risk of osteoarthritis or other arthritic conditions.

If you already have arthritis, cracking might not worsen it, but caution is advised. In weakened joints, the action could theoretically increase risks of acute trauma or ligament injury, though this is rare and unproven in practice. Recent analyses highlight that while the myth persists, radiographic studies and clinical reviews show no causal link.

Potential Side Effects and Risks: Beyond the Myth

While the arthritis link is a myth debunked, knuckle cracking isn’t entirely harmless, especially for habitual knuckle crackers. Research indicates possible long-term effects on hand health. For instance, a study of chronic crackers found they were more prone to hand swelling and reduced grip strength compared to non-crackers. This could stem from repeated stress on the joint capsule, potentially leading to cartilage thickening or minor functional hand impairment over years.

Rare reports in medical literature link cracking to ligament injury or tendon dislocations, which typically resolve with conservative treatment. In one case involving a young person, habitual cracking was associated with knuckle pads—thickened skin over the joints. Age doesn’t seem to alter the mechanics significantly, though children and adults alike should avoid forceful cracking to prevent any joint damage. Additionally, while not common, some individuals may experience rare soft-tissue irritations from excessive cracking, such as minor inflammation around the joints.

The force involved in cracking has been measured in lab studies and exceeds thresholds that could theoretically harm cartilage, but real-world evidence shows no degenerative arthritis from this habit. Still, if cracking causes pain, it’s wise to stop, as it might signal underlying issues. The majority of studies find no link between knuckle cracking and osteoarthritis or joint swelling, but monitoring for personal discomfort remains key.

Why Do People Crack Their Knuckles, and Should You Stop?

People often develop a cracking habit for the temporary relief it provides—joints feel looser, and the popping sound can be satisfying, almost addictive. As children, some start for the novelty of the noise. Psychological factors, such as stress relief or habit formation, also play a role, with some viewing it as a form of self-soothing similar to other repetitive behaviors.

However, if it’s annoying to others or becomes compulsive, breaking the habit might improve social interactions without health trade-offs. Techniques to stop include mindfulness practices, using stress balls, or consciously keeping hands occupied. For those concerned about long-term effects, consulting a healthcare professional can provide personalized advice, especially if there’s family history of joint issues.

In summary, knuckle cracking does not cause arthritis, whether osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis. Extensive research on joint mechanics, synovial fluid dynamics, and long-term studies of habitual knuckle crackers consistently shows no link to joint damage or inflammatory arthritides. While minor risks like reduced grip strength or hand swelling exist, they’re not universal and pale compared to the myth’s exaggeration. For optimal hand health, listen to your body: if it hurts, stop. This evidence-based perspective empowers you to crack—or not—without undue worry, fostering trust in science over folklore.