In the Catholic Church, the seal of confession is an unbreakable rule of secrecy that prevents priests from ever revealing sins confessed during the sacrament of penance, including serious crimes like murder. This sacramental seal ensures absolute clergy confidentiality, allowing penitents to seek absolution and spiritual healing without fear of betrayal. Rooted in canon law, any violation brings automatic excommunication, and priests throughout history have chosen martyrdom over breaking it. Theologically, it encourages honest repentance by prioritizing divine forgiveness over earthly justice. In many countries, priest-penitent privilege protects this in court, though it sometimes conflicts with mandatory reporting laws for abuse. Priests can withhold absolution for unrepentant sins or future crimes and urge self-reporting, but they cannot disclose past confessed sins. This inviolable seal balances religious freedom with public safety debates, remaining a core Catholic doctrine today.

Long Version

The Seal of Confession: Why Priests Cannot Reveal Murders and Other Confessed Sins

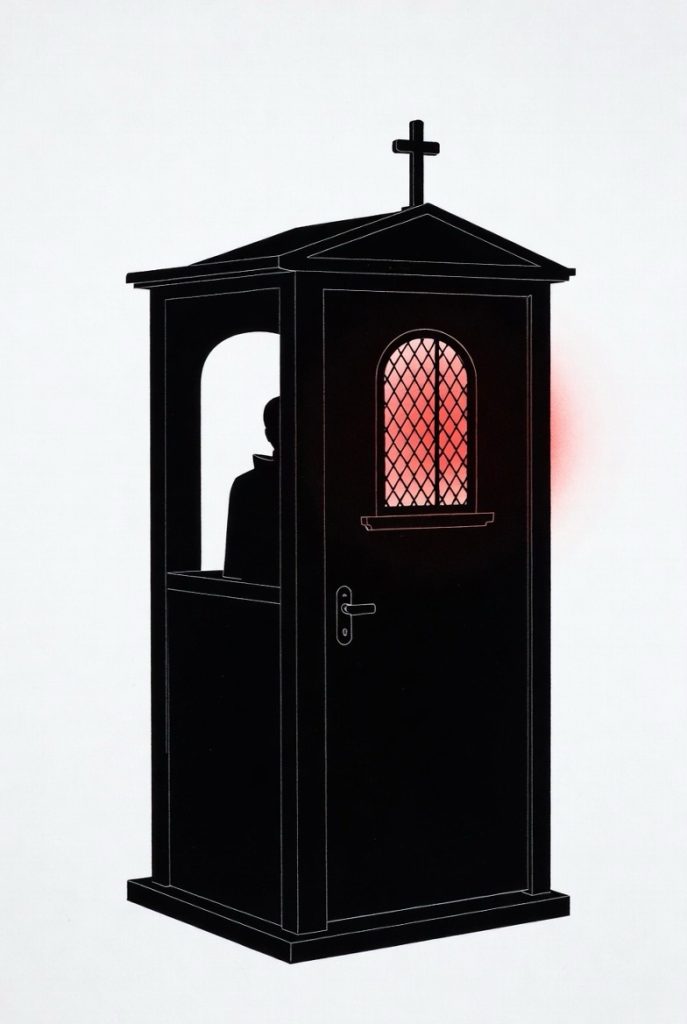

In the Catholic Church, the sacrament of penance—often simply called confession—serves as a profound channel for spiritual healing. Here, a penitent confesses sins to a priest, seeking absolution and reconciliation with God. Central to this rite is an unbreakable vow of secrecy known as the seal of confession, or sacramental seal. This confessional seal ensures that no priest can ever betray the penitent by revealing what was shared, even in cases involving grave crimes like murder. This principle, rooted in centuries of church tradition and canon law, underscores the inviolable nature of clergy confidentiality, prioritizing the penitent’s trust in the confessor above all else.

Theological Foundations of the Seal

The seal of the confessional stems from the Catholic understanding of sin and forgiveness. When a penitent approaches a priest in confession, they are not merely speaking to a human intermediary but engaging in a divine encounter. The priest, acting as confessor, grants absolution in the name of Christ, absolving the penitent of their sins. This process demands absolute confidentiality to encourage honest repentance; without it, the sacrament of penance would lose its efficacy. The church teaches that revealing confessed sins would betray the penitent’s vulnerability and undermine the spiritual bond between God and the individual. Even for heinous acts like murder, the seal remains intact, as the focus is on spiritual redemption rather than earthly justice. This clergy confidentiality extends beyond the confessor to anyone who might overhear, reinforcing the seal’s inviolable status.

To deepen this understanding, consider how the seal aligns with broader theological principles. The sacrament emphasizes mercy and transformation, allowing individuals to confront their failings in a safe space. Without the assurance of secrecy, fear of exposure could deter people from seeking forgiveness, potentially leading to unaddressed spiritual harm. This foundation draws from scriptural references, such as the authority given to apostles to forgive sins, interpreted by the church as requiring utmost discretion to mirror divine compassion.

Canon Law and Its Strict Enforcement

Under Catholic canon law, the seal of confession is explicitly defined and protected. The relevant canon states that the sacramental seal is inviolable; therefore, it is absolutely forbidden for a confessor to betray in any way a penitent in words or in any manner and for any reason. Violation of this rule incurs automatic excommunication latae sententiae, a severe penalty that can only be lifted by the Apostolic See in most cases. This underscores the church’s commitment to secrecy, viewing any breach as a profound betrayal of trust. For instance, a priest cannot use knowledge from confession to influence external actions, even indirectly, without risking this excommunication. The law applies universally within the Catholic Church, ensuring that no confessor can reveal details of a crime, such as murder, confessed during the sacrament.

Enhancing this section, it’s worth noting that canon law also addresses indirect violations, such as hinting at confessed matters in sermons or conversations. Priests are trained extensively on these boundaries during seminary education, with ongoing formation to handle ethical dilemmas. In rare cases where a penitent seeks to waive the seal—for example, to prove innocence in a legal matter—the church still prohibits disclosure, as the seal belongs to the sacrament itself, not the individual.

Historical Martyrs and the Seal’s Endurance

Throughout history, numerous priests have chosen death over violating the seal of the confessional, becoming martyrs for this principle. A 14th-century Bohemian priest was tortured and drowned for refusing to disclose the confessions of a queen to her jealous husband. In the 20th century, during a period of religious conflict in Mexico, a priest was executed after hearing confessions from rebel prisoners and declining to reveal their contents to government forces. Similarly, during another civil war in the 1930s, several priests were martyred for upholding the seal amid persecution. Another example from the early 19th century involves a priest who met a similar fate during a war of independence in South America. These stories illustrate the seal’s deep-rooted inviolability, where priests have faced martyrdom rather than betray the penitent.

To enhance the historical perspective, these martyrs often drew inspiration from early church fathers who emphasized confidentiality in pastoral writings. Over time, the seal evolved from a moral imperative to a codified law by the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215, which mandated annual confession and reinforced secrecy to promote widespread participation in the sacrament.

Legal Recognition and the Priest-Penitent Privilege

In secular law, the concept aligns with the priest-penitent privilege, which protects confidential communications between clergy and penitents in many jurisdictions. Originating from common law traditions, this privilege recognizes the importance of religious confidentiality, often treating it on par with attorney-client or doctor-patient protections. In various countries, including the United States where all states acknowledge some form of this privilege, its scope varies but generally upholds the right to withhold confessional information in court. For example, early legal precedents upheld a priest’s refusal to testify about a confession involving stolen goods, citing the free exercise of religion. However, the privilege typically requires that the communication be made in a confidential, spiritual context, and it does not extend to non-penitential conversations.

Expanding on this, international variations exist; in some European countries, the privilege is embedded in constitutional protections for religious freedom, while in others, it may be more limited. Courts often weigh the privilege against compelling state interests, but religious protections frequently prevail in confessional matters.

Conflicts with Mandatory Reporting Laws

Tensions arise when the seal intersects with secular laws on crime reporting. Mandatory reporting statutes require certain professionals, including clergy in some regions, to disclose knowledge of child abuse or neglect. While these laws often carve out exceptions for confessional communications, debates persist, especially regarding serious crimes like murder. In places like Australia and certain U.S. states, governments have pushed to mandate reporting of confessed abuses, leading to court battles. The Catholic Church staunchly opposes such measures, arguing they infringe on religious freedom and would deter penitents from seeking absolution. Priests have stated they would face imprisonment or martyrdom before breaking the seal. Notably, the privilege does not cover future crimes; if a penitent confesses intent to commit murder, the priest may withhold absolution and encourage turning themselves in, but cannot directly reveal the confession.

For enhancement, recent discussions as of late 2025 highlight ongoing legislative efforts in several jurisdictions to refine these laws, often resulting in compromises that respect religious exemptions while strengthening protections for vulnerable populations. Ethical guidelines for priests now include strategies for guiding penitents toward voluntary disclosure without breaching confidentiality.

Clarifying Common Misconceptions

Popular culture often dramatizes the seal, as in films where a priest is framed for murder but cannot reveal the true culprit due to confessional secrecy. However, misconceptions abound. The seal applies only to past sins confessed for absolution; plans for future crimes fall outside its protection, allowing priests to act preventively without betrayal. Additionally, a priest cannot absolve someone unwilling to make amends, such as by confessing to authorities for a murder. If a priest violates the seal, even another confessor cannot grant absolution without higher authority, emphasizing its gravity. Anonymous confessions further complicate reporting, as priests often lack identifying details.

To clarify further, the seal does not prevent priests from addressing systemic issues, like urging church reforms on abuse prevention, as long as specific confessional details remain undisclosed. This distinction helps maintain the sacrament’s integrity while allowing for broader accountability.

Modern Debates and Implications

Contemporary discussions highlight the seal’s role in balancing spiritual confidentiality with public safety. Critics argue it shields criminals, particularly in abuse cases, while proponents insist it fosters repentance and prevents greater spiritual harm. In various regions, bills have sought to compel reporting, but the church maintains the seal’s inviolability. Ultimately, this doctrine reflects the Catholic Church’s view that divine law supersedes human mandates, ensuring penitents can approach confession without fear of betrayal. For priests, upholding this secrecy is not just a rule but a sacred duty, even in the face of legal or personal peril.

Enhancing the conclusion, modern implications extend to interfaith dialogues, where similar confidentiality principles in other religions, like pastoral counseling in Protestant traditions, face parallel challenges. As societies grapple with transparency and justice, the seal remains a testament to the enduring tension between faith and law, encouraging ongoing reflection on how best to protect both spiritual and societal well-being.