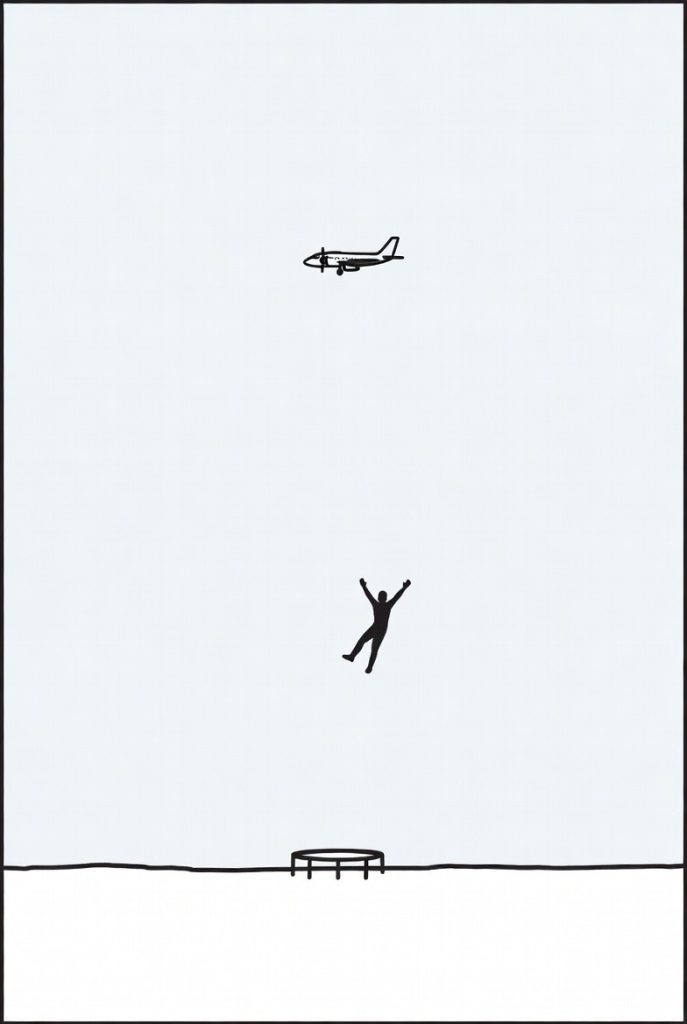

Jumping from a plane and landing safely on a trampoline sounds exciting, but physics shows it’s nearly impossible. In free fall from typical skydiving heights, you reach terminal velocity around 120 mph due to gravity and air resistance, building massive kinetic energy. Hitting a trampoline at that speed creates extreme impact forces and g-forces far beyond human tolerance—often over 50g, causing severe injury or death. Trampolines rely on elasticity to stretch and bounce, but standard ones would rip, snap springs, or fail under such force. Even a perfect unbreakable trampoline couldn’t decelerate you gently enough without enormous depth, and rebounds would still be dangerous. Real survival from high falls is rare and usually involves luck or special equipment like parachutes or large safety nets. The safest way to jump from a plane? Always use a parachute—physics demands it.

Long Version

Could a Trampoline Catch You from a Plane? A Deep Dive into the Physics of Survival

The idea of jumping from a plane and landing safely on a trampoline has captured imaginations for years, often surfacing in thought experiments and heated debates. It’s a scenario that blends thrill-seeking adventure with raw physics, prompting questions about whether such a dramatic survival is feasible. While it sounds like something out of a Hollywood stunt, the reality hinges on fundamental principles like gravity, energy, and force. In this article, we’ll dissect every angle—from the mechanics of free fall to the limits of trampoline elasticity—to determine if this high-stakes bounce could ever lead to a safe landing. We’ll explore the underlying science in greater detail, including mathematical insights and real-world analogies, to provide a thorough understanding.

The Dynamics of Falling from a Plane

To understand if a trampoline could catch someone plummeting from a plane, we first need to grasp the physics of the fall itself. Imagine leaping from a cruising aircraft at a typical skydiving height of around 10,000 meters. Without any intervention, gravity takes over immediately, pulling you downward with a constant gravitational acceleration of about 9.81 m/s². This is free fall in its purest form, where your velocity increases rapidly due to unchecked acceleration.

However, air resistance—or wind resistance—quickly comes into play, counteracting gravity as you gain speed. This drag force depends on your body’s orientation, surface area, and the air’s density. For a person in a belly-to-earth position, terminal velocity is reached when these opposing forces balance, typically around 53 meters per second (about 120 mph). At this point, you’re no longer accelerating; you’re falling at a constant speed. From such a height, you’d hit terminal velocity long before impact, carrying immense kinetic energy—roughly 105,337 joules for a 75 kg person, equivalent to the energy of a small car crashing at highway speeds. To calculate this, recall that kinetic energy (KE) is given by KE = (1/2)mv², where m is mass and v is velocity. Plugging in the values: (1/2) * 75 * (53)² ≈ 105,337 J.

Without air resistance, the scenario is even more dire. Velocity from 10,000 meters would soar to over 442 m/s (nearly 1,000 mph), derived from v = √(2gh), where g is gravitational acceleration and h is height. But thankfully, real-world falls include this mitigating factor. Still, the height, velocity, and energy involved make any uncontrolled landing a recipe for disaster, far beyond everyday jumps or crashes. Air currents can influence trajectory slightly, but they do little to reduce the overall energy buildup.

The Impact: Forces and Energy at Play

Upon hitting the ground—or in this case, a trampoline—the real challenge is managing the impact. Your kinetic energy from the fall must be dissipated safely to avoid catastrophic injury. This involves rapid deceleration, where the surface absorbs and redirects that energy.

Impact forces are governed by Newton’s laws: the shorter the stopping distance, the greater the force. For a terminal velocity fall, stopping over just a few meters would generate deceleration of around 702 m/s², translating to over 71 g-forces. This can be estimated using the work-energy principle: force * distance = kinetic energy, so F = KE / d, where d is the stopping distance. For d = 2 meters, F ≈ 52,668 N, or about 71 times the person’s weight (since g-force = F / (mg)). Human tolerance for g-forces is limited—sustained exposure above 50g often leads to blackouts, organ damage, or death, as the body can’t handle the intense compression and shear stresses. Blood pooling, bone fractures, and internal hemorrhaging are common outcomes in such scenarios.

Energy transfer is key here. The fall’s kinetic energy converts to potential energy in the trampoline’s deformation, but if not managed, it could result in a violent rebound. In essence, the crash isn’t just about surviving the initial hit; it’s about controlling the entire energy exchange to prevent lethal acceleration. Factors like body position can mitigate some risks—a feet-first landing distributes force better than a flat impact—but even optimal alignment can’t overcome the raw numbers.

How Trampolines Work: Elasticity and Limits

Trampolines are designed for fun bounces, not life-saving catches from extreme heights. Their core mechanism relies on elasticity, following Hooke’s law, which states that the force exerted by a spring (or fabric) is proportional to its deformation: F = -kx, where k is the spring constant and x is displacement. When you land, the mat stretches, storing potential energy in the springs and fabric (PE = (1/2)kx²), then releases it to propel you upward in harmonic oscillations—a series of bounces that gradually dissipate energy through friction and air resistance.

A standard trampoline might handle a double bounce from a few meters, but scaling up to a plane fall exposes its limits. The fabric could rip under the immense impact forces, springs might snap from overload, and metal poles could bend or buckle. Even assuming an unbreakable trampoline with no stretch limit, the rapid deformation would still impose deadly g-forces unless the depression is extraordinarily deep—perhaps dozens of meters—to allow gradual deceleration. For context, to limit g-forces to 10g, the stopping distance would need to be about 14 meters, based on v² = 2ad, where a = 10g ≈ 98 m/s².

Materials like high-strength spectra fabric or reinforced designs might extend the stretch limit, but real trampolines aren’t built for this. In simulations of high falls, the energy transfer often leads to uncontrolled rebounds, where the person oscillates wildly, risking further injury on subsequent landings. The concept of energy dissipation through multiple bounces assumes perfect elasticity, but real systems lose energy inefficiently, potentially leading to chaotic motion.

Why Survival Is Unlikely: Breaking Down the Myths

Despite the allure, physics overwhelmingly suggests that a trampoline couldn’t safely catch you from a plane. Even in hypothetical scenarios with an unbreakable trampoline over an endless pit, the rebound would launch you back up at a significant fraction of terminal velocity, converting kinetic energy to potential and back without full dissipation. You’d bounce repeatedly, but the initial deceleration could still shatter bones or rupture organs. Mathematical modeling shows that for elastic collisions, the rebound velocity approaches the incoming velocity, minus minor losses, making repeated high-g exposures inevitable.

Real-world discussions highlight these flaws. For instance, specialized safety nets engineered for gradual energy absorption might work in controlled stunts, but a typical trampoline falls short. Claims of successful high-fall bounces are often exaggerated or simulated, relying on lower heights or added safeguards rather than pure physics. Moreover, factors like landing angle complicate matters. A rollover maneuver mid-air might help align your body, but imprecise hits could cause glancing blows, amplifying damage. Compressed air cylinders or other gadgets aren’t standard in this context and wouldn’t alter the core physics without significant engineering.

Alternatives and Real-World Insights

If trampolines are out, what about proven safety measures? Parachutes remain the gold standard in skydiving, deploying to slash velocity through increased air resistance, allowing controlled landings at under 5 m/s. Safety nets, as in circus acts or specialized stunts, offer better odds by distributing impact over a larger area and deeper deformation, effectively increasing the stopping distance.

Remarkable survival stories exist, like individuals enduring high falls cushioned by wreckage, snow, or other soft materials. But these are anomalies, not blueprints. Controlled experiments have tested similar ideas but consistently affirm that without engineered deceleration, survival odds plummet. These tests often use dummies or scaled models to measure forces, revealing that even minor increases in height exponentially raise risks.

Conclusion: Prioritizing Safety Over Spectacle

In the end, the notion of a trampoline catching you from a plane is a fascinating thought experiment, but one grounded in insurmountable physical barriers. From the relentless pull of gravity and buildup of kinetic energy during free fall, to the brutal impact forces and limitations of trampoline elasticity, every aspect points to near-certain failure. While unbreakable designs or advanced materials might intrigue theorists, practical safety demands reliable tools like parachutes.

This analysis underscores a broader lesson: adventure sports like skydiving thrive on calculated risks, not myths. Always prioritize professional training, equipment, and respect for physics to ensure survival isn’t left to chance. For those curious about the boundaries of human endurance, consult experts and verified sources—because in the realm of high-altitude jumps, knowledge is the ultimate safety net.