Mercury pollution enters waterways from coal plants, volcanoes, gold mining, and other sources. In sediments, bacteria convert it to toxic methylmercury (MeHg), which builds up in fish through bioaccumulation and biomagnification—levels rise dramatically in larger predatory fish like swordfish, tuna, and shark as they eat smaller ones. This poses serious health risks, especially neurotoxicity from prenatal or childhood exposure, potentially affecting brain development, cognition, and motor skills. Adults may face milder issues at high doses. To stay safe, follow consumption advisories: limit or avoid high-mercury predatory fish, especially if pregnant, breastfeeding, or feeding young children. Instead, choose low-mercury options like salmon, shrimp, sardines, or anchovies to get valuable omega-3 fatty acids for heart and brain health without the risk. Reducing emissions and smarter seafood choices help protect both people and wildlife from this persistent environmental threat.

Long Version

Understanding Mercury Contamination in Seafood: Sources, Risks, and Safe Choices

Mercury pollution represents a significant environmental challenge, infiltrating aquatic ecosystems and posing toxicity concerns for both wildlife and humans. This heavy metal enters water bodies through various pathways, including emissions from coal plants and natural releases from volcanoes, where it undergoes bacterial conversion into the highly toxic form known as methylmercury (MeHg, or CH3Hg+). Once formed, methylmercury accumulates in fish through bioaccumulation and biomagnification processes as larger predatory fish consume smaller ones in the food webs. Health risks from consuming contaminated seafood are well-documented, prompting consumption advisories that recommend avoiding long-lived predators like swordfish while opting for lower-risk options such as salmon or shrimp to obtain essential omega-3 fatty acids without the dangerous mercury load.

Sources of Mercury Pollution

Mercury contamination in water arises from a mix of anthropogenic sources and natural processes. Anthropogenic sources, which dominate global emissions, include coal-fired power plants that release mercury into the atmosphere during combustion, contributing to widespread pollution. Other point sources encompass industrial activities like gold mining, where mercury is used in extraction and often discharged into rivers, and chlor-alkali plants or cement production facilities. Non-point sources, such as deforestation, exacerbate the issue by mobilizing mercury from soils through erosion and increased organic matter runoff, altering water chemistry and facilitating further contamination. Wastewater from municipalities, dental clinics, and petrochemical operations also introduces mercury, with petroleum-related discharges being notable in certain regions.

Natural sources play a role as well, with volcanoes emitting mercury directly into the atmosphere or through geothermal activity, accounting for a portion of the global biogeochemical cycles. Geological deposits and weathering of rocks release mercury into soils and waters, while earthquakes and ocean upwelling can redistribute it in marine environments. Atmospheric deposition is a key mechanism, where volatilization allows elemental mercury to travel long distances before depositing via wet or dry processes onto lands and water bodies, linking distant sources to local contamination. Overall, these emissions—whether from human activities or natural events—integrate into broader biogeochemical cycles, cycling mercury between air, soil, and water in ways that amplify its environmental persistence. To enhance understanding, note that recent advancements in monitoring have revealed how climate change influences these cycles, potentially increasing methylation rates in warming waters and thawing permafrost, which releases stored mercury.

The Transformation Process: Bacterial Methylation

Once mercury enters aquatic ecosystems, it doesn’t remain inert. In anaerobic conditions prevalent in sediments, wetlands, and deeper water layers, bacteria—particularly sulfate-reducing bacteria and iron-reducing ones—convert inorganic mercury into methylmercury through a process called bacterial methylation. This transformation is influenced by environmental factors such as low pH, high sulfate concentrations, and the presence of dissolved organic carbon (DOC), which binds mercury and facilitates its uptake by microbes. Sulfate reduction plays a critical role, as these anaerobic bacteria use sulfate as an electron acceptor, inadvertently methylating mercury in the process.

In marine and freshwater settings, methylation often outpaces demethylation—the breakdown of methylmercury via photodecomposition or microbial action—especially in sulfur-rich, oxygen-poor sediments. This imbalance drives the accumulation of MeHg, integrating it into the biogeochemical cycles where it becomes bioavailable to organisms at the base of food webs. For added depth, research indicates that microbial communities can vary by ecosystem, with certain archaea also contributing to methylation in extreme environments like deep-sea vents, highlighting the complexity of these biochemical pathways.

Bioaccumulation and Biomagnification in Aquatic Ecosystems

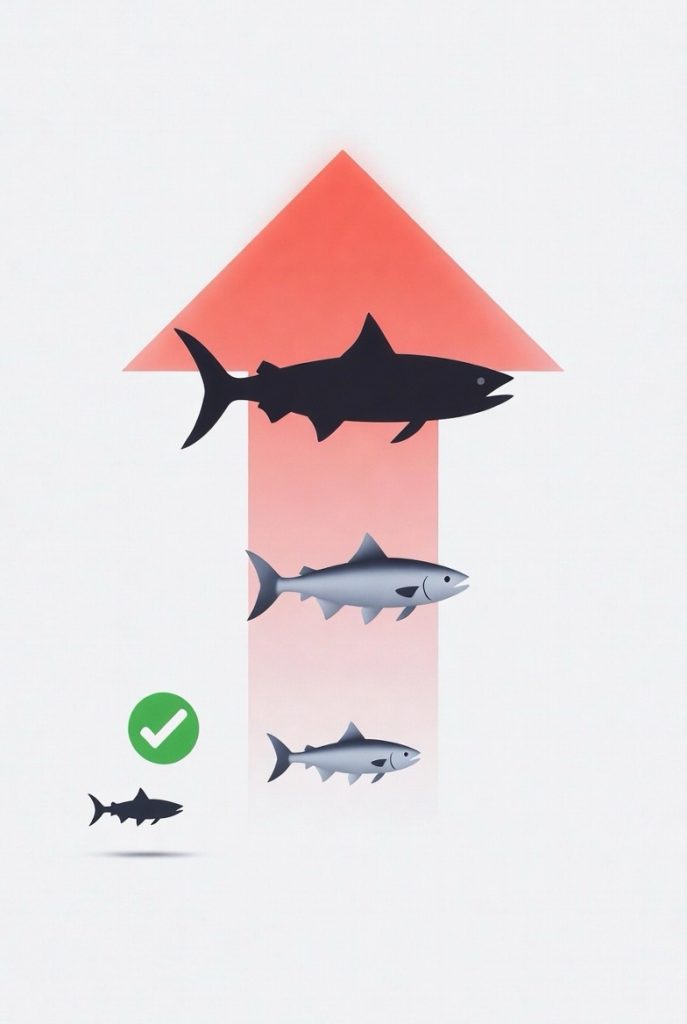

Methylmercury’s danger escalates through bioaccumulation, where it builds up in the tissues of aquatic organisms, and biomagnification, which intensifies concentrations as it moves up trophic dynamics in food webs. Low-trophic level species like zooplankton or small fish absorb MeHg from water or sediment, but levels surge in predatory fish that consume them, such as tuna or sharks. Factors like fish size, age, habitat (benthic versus pelagic), and seasonal variations influence accumulation, with larger, long-lived predators exhibiting the highest loads due to their position in the trophic chain.

This process affects entire aquatic ecosystems, potentially disrupting biodiversity and impacting wildlife, including seabirds and marine mammals that rely on contaminated prey. Invasive species can further complicate dynamics by altering food webs and mercury transfer pathways, though their specific impacts vary by ecosystem. Enhancing this section, it’s worth noting that biomagnification factors can exceed 10-fold per trophic level in some systems, leading to concentrations in top predators that are millions of times higher than in surrounding water, underscoring the efficiency of these ecological processes.

Health Risks Associated with Mercury Exposure

Exposure to methylmercury primarily occurs through seafood consumption, where it is absorbed at rates up to 95% and crosses the blood-brain barrier, leading to neurotoxicity. Vulnerable groups face heightened risks: prenatal exposure during fetal development can impair neurological development, causing cognitive deficits, motor skill issues, and reduced intelligence, while postnatal exposure in children may lead to attention problems and developmental delays. Adults might experience symptoms like memory loss, muscle weakness, or sensory impairments at high doses, though typical seafood intake rarely reaches these levels.

Historically, events like Minamata disease in Japan highlighted mercury’s devastation, where industrial discharges caused widespread neurological harm through contaminated fish. Broader effects include potential links to cardiovascular health issues, though research emphasizes net benefits from moderate fish consumption. The reference dose (RfD) for MeHg defines safe exposure limits—typically 0.1 µg/kg body weight per day—to prevent adverse outcomes. The selenium-to-mercury ratio (Se:Hg) in fish can mitigate toxicity, as selenium forms protective complexes, but imbalances heighten risks in high-mercury species. To enhance, emerging studies suggest that chronic low-level exposure may also affect immune function and endocrine systems, prompting ongoing research into long-term population health impacts.

Consumption Advisories and Guidelines

To address these health risks, agencies issue detailed consumption advisories. Guidelines for water quality and fish tissue criteria identify impaired waters and develop Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs) to cap mercury inputs, often focusing on atmospheric deposition from regional and global sources. Advisories target vulnerable populations—those pregnant, breastfeeding, or with young children—recommending limits on high-mercury fish to balance nutrients and risks.

Specific advice urges avoiding predatory fish like swordfish, which accumulate high MeHg levels, while many regions issue local alerts for contaminated waters. Monitoring programs track levels to inform these guidelines, ensuring public health protection. For enhancement, international standards have evolved to include more species-specific data, incorporating factors like fish origin (wild vs. farmed) to provide tailored recommendations.

Safe Alternatives: Getting Omega-3s Without the Risk

Despite risks, seafood remains a vital source of omega-3 fatty acids, which support cardiovascular health, brain development, and immune function. To reap these benefits safely, choose low-mercury options like salmon or shrimp, which offer substantial omega-3s with minimal contamination. These species, often lower in the trophic chain, provide nutritional value without the elevated MeHg load found in top predators. Additionally, plant-based alternatives like flaxseeds or algae supplements can supply omega-3s for those avoiding seafood entirely, broadening safe options.

Broader Impacts and Mitigation

Beyond humans, mercury affects wildlife through similar bioaccumulation pathways, causing oxidative damage and population declines in sensitive species. Mitigation involves reducing emissions from key sources, enhancing wastewater treatment, and international agreements to curb global mercury use. Strategies like wetland restoration can also trap mercury before it enters food webs, while technological innovations in power plants, such as advanced scrubbers, further decrease atmospheric releases.

In summary, mercury’s journey from sources like coal plants and volcanoes to toxic methylmercury in fish underscores the need for informed choices. By adhering to guidelines and selecting safer seafood, individuals can minimize health risks while enjoying essential nutrients, fostering trust in science-based environmental management.