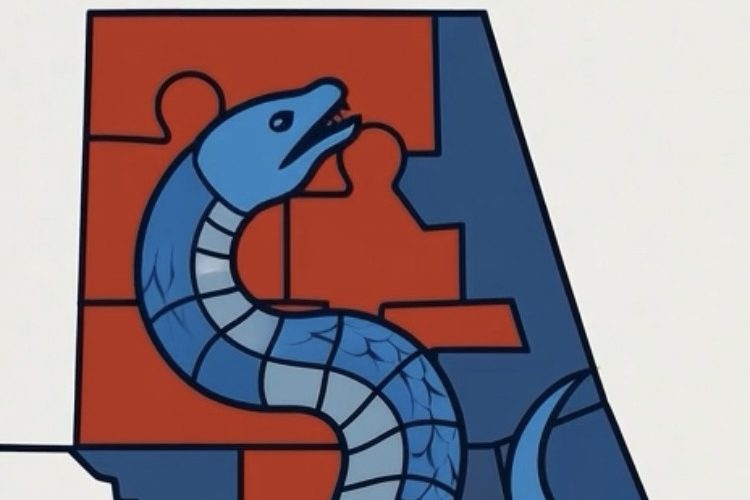

Gerrymandering is the manipulation of electoral district boundaries to favor one party or group, often using census data during redistricting led by state legislatures. Named after Elbridge Gerry’s 1812 salamander-shaped district, it undermines fair representation and voting rights, especially for communities of color. Common tactics include packing (concentrating opponents into few districts) and cracking (spreading them to dilute power), plus hijacking and kidnapping incumbents. Types include partisan (for party gain), racial (targeting race), bipartisan (protecting incumbents), and prison-based (counting inmates at prisons, boosting rural power). Detection uses efficiency gap, seats-votes curve, compactness tests, and simulation models. The Voting Rights Act fights racial gerrymandering, but partisan cases are often nonjusticiable. It reduces competition, increases polarization, and skews policy. Reforms like independent commissions, fair algorithms, and proportional voting help ensure equal, honest representation.

Long Version

Understanding Gerrymandering

Gerrymandering manipulates electoral boundaries to favor specific political parties or groups, distorting fair representation in American democracy. Named after Elbridge Gerry, who approved a salamander-shaped district in 1812, it relies on census data for redistricting by state legislatures, often undermining voting rights and equitable outcomes for communities of color.

Historical Background

Gerrymandering parallels 19th-century Britain’s rotten boroughs, where malapportionment gave sparse areas undue influence. In the U.S., 1960s Supreme Court rulings enforced the one person, one vote principle, mandating equal-population districts. However, this spurred advanced techniques using data analytics and geographic systems to predict voter behavior precisely, evolving beyond basic population compliance.

Techniques and Tactics

Core methods include packing, which clusters opposition voters into few majority-minority districts, and cracking, which spreads them to dilute strength. Advanced tactics like hijacking force incumbents to compete, while kidnapping shifts their voter base. These exploit residential segregation and racially polarized voting, enabling subtle targeting without overt racial gerrymandering violations. Sweetheart gerrymandering protects cross-party allies.

Types of Gerrymandering

Partisan gerrymandering creates safe seats and wasted votes, benefiting the dominant party. Racial gerrymandering discriminates by race, sometimes via affirmative gerrymandering to empower minorities. Bipartisan gerrymandering involves party collaboration for incumbent protection. Prison-based gerrymandering counts inmates at prison sites, inflating rural districts and skewing resources from urban minority areas.

Detection Methods

Quantitative tools assess fairness: the efficiency gap measures wasted vote disparities, while the seats-votes curve reveals bias in seat allocation. Geometric metrics like convex hull and isoperimetric quotient flag irregular shapes. Markov chain Monte Carlo simulations compare maps against alternatives, providing bias evidence for challenges.

Legal Framework

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 bans minority vote dilution, targeting racial gerrymandering in discriminatory areas. Key rulings deem partisan claims nonjusticiable, deferring to states, but allow scrutiny of mid-decade redistricting motives. State constitutions and initiatives impose compactness standards, fueling ongoing litigation amid post-2020 census shifts.

Impacts on Democracy

Gerrymandering erodes trust by reducing competition and entrenching parties, fostering polarization through extreme candidates. It fragments communities of color, suppressing turnout and underrepresentation. Economically, it skews policies toward gerrymandered interests, ignoring broader needs like infrastructure. Recent mid-decade efforts highlight conflicts driven by migration and urbanization.

Reform Efforts

Independent redistricting commissions prioritize compactness and community integrity, yielding balanced maps in adopting states. Algorithmic fair division, like I-cut-you-choose, promotes equity. Alternatives such as ranked-choice voting or proportional representation align seats with vote shares. Grassroots campaigns and referendums drive anti-gerrymandering measures.

Conclusion

Gerrymandering challenges democratic ideals by turning boundaries into power tools. Grasping its tactics and metrics empowers advocacy for fair representation. Vigilance in redistricting cycles is essential to ensure inclusive governance and equal vote weight.