Mary Bateman, known as the Yorkshire Witch, was a shrewd early 19th-century con artist from northern England who masterfully exploited superstition and vulnerability for profit. Born in 1768, she evolved from petty thefts in her youth to elaborate frauds in Leeds, posing as a mystic under aliases to sell fake prophecies, charms, and remedies while tapping into religious anxieties. Her most infamous scheme, the Prophet Hen of Leeds hoax in 1806, used a simple vinegar chemical trick to etch apocalyptic messages like “Crist is coming” onto eggshells, reinserting them for the hen to “lay,” which drew eager crowds and substantial earnings. Her deceptions later turned deadly, including poisoning clients such as the Perigos with toxic substances to sustain the scams. Arrested in 1808, convicted of fraud and murder, and executed in 1809, Bateman’s story remains a compelling cautionary tale about the power of manipulation and the importance of skepticism in the face of extraordinary claims.

Long Version

The Yorkshire Witch: Unveiling the Cunning Legacy of Mary Bateman

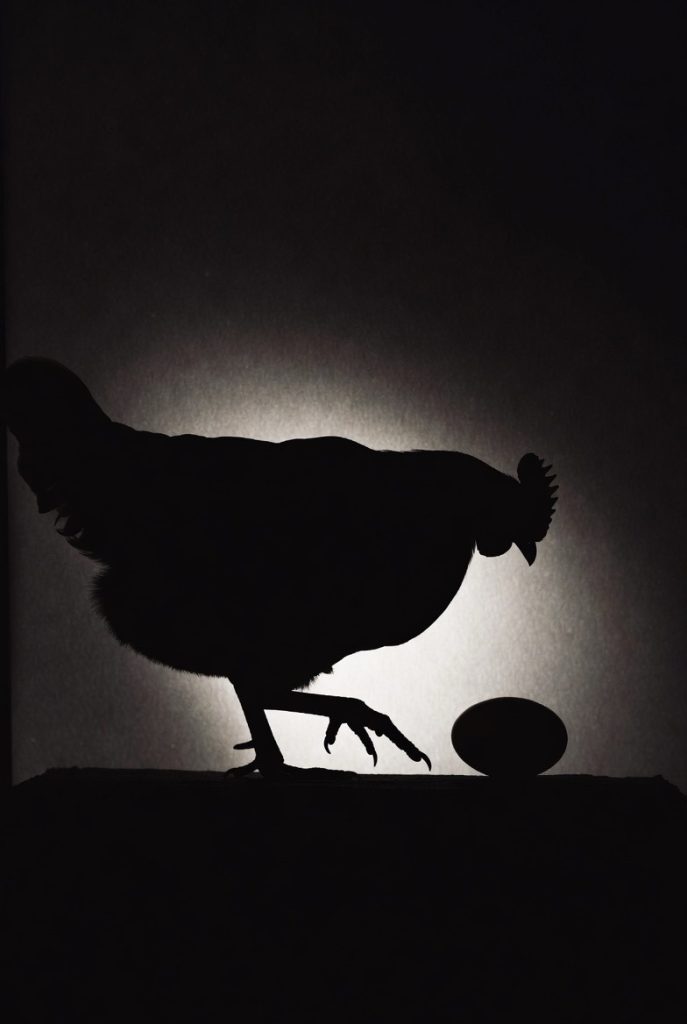

In the turbulent early 19th century, when superstition intertwined with everyday hardships in northern England, one woman’s elaborate deceptions left an indelible mark on history. Mary Bateman, infamously known as the Yorkshire Witch, masterminded schemes that exploited fear, faith, and folly, culminating in her most audacious feat: a hen that seemingly laid eggs foretelling doom. Through a clever chemical trick, she inscribed messages like “Crist is coming” on eggs, igniting widespread panic and profit. This comprehensive exploration uncovers every facet of Bateman’s life, from her humble origins to her notorious scams, offering fresh perspectives on how such frauds reveal timeless human susceptibilities and providing practical insights for recognizing similar manipulations today.

Born Mary Harker in 1768 to a farming family in the quiet village of Asenby, North Yorkshire, Bateman’s early years hinted at the resourceful yet restless spirit that would define her. Growing up in a rural setting where education was a privilege, she acquired basic literacy skills that set her apart. At around 13, she entered domestic service in nearby Thirsk, a common path for young women of her class. However, her time there ended abruptly due to suspicions of minor thefts, marking the first documented instance of her inclination toward dishonesty. Undeterred, Bateman ventured to York and then Leeds by her late teens, drawn to the anonymity and opportunities of urban life amid England’s industrial stirrings. In Leeds, a thriving textile hub plagued by poverty and uncertainty, she initially worked as a mantua maker, crafting dresses while quietly building a side hustle in petty frauds.

Her marriage to John Bateman, a wheelwright, in the early 1790s brought a semblance of stability, with the couple raising several children. Yet, this domestic facade masked her escalating criminal activities. Frequent relocations across Yorkshire helped her evade detection, as she transitioned from simple thefts to more intricate cons. Bateman’s charisma and quick wit allowed her to pose as a “wise woman,” tapping into the era’s blend of folklore and emerging rationalism. This period solidified her reputation as the Leeds witch, a figure who blurred the lines between helpful healer and sinister sorceress, preying on a society still haunted by echoes of earlier witch hunts.

Forging a Path of Deception: Early Frauds and Fortune-Telling Ventures

Mary Bateman’s initial forays into fraud were modest but methodical, reflecting her keen understanding of human vulnerabilities. She began by offering fortune-telling services, using invented aliases like Mrs. Moore and Mrs. Blythe to create an aura of mystique. These personas enabled her to solicit payments for prophecies, charms, and potions without direct blame if they failed. Clients, often from lower classes grappling with illness or misfortune, sent valuables to these fictitious intermediaries, believing they secured protection from curses or bad luck. Bateman’s schemes exploited the limited access to formal medicine, positioning her as an alternative authority in a time when quackery was commonplace.

As her confidence grew, so did the sophistication of her witch scams. She aligned with religious undercurrents, drawing from millenarian groups like the Southcottians, who anticipated apocalyptic events. In Leeds, where economic disparities fueled desperation, Bateman sold “remedies” that were essentially harmless mixtures, sometimes with added flair to mimic supernatural effects. Historical accounts suggest she may have assisted with sensitive personal matters, such as unwanted pregnancies, further embedding her in community secrets. Beyond the occult, she engaged in opportunistic thefts, like collecting donations after local calamities—such as fires—under false pretenses of aiding victims. These acts demonstrated her adaptability, blending supernatural allure with straightforward deceit to maximize gains.

What set Bateman apart as a witch con artist was her psychological acumen. She crafted narratives that resonated deeply, turning clients’ fears into profitable dependencies. In an era lacking widespread skepticism, her methods thrived, illustrating how false prophecy hoaxes can flourish when trust outpaces verification. This phase of her life underscores a broader insight: deception often succeeds not through complexity but by mirroring societal beliefs, a pattern seen in various historical scams.

The Pinnacle of Audacity: The Prophet Hen of Leeds Hoax

The 1806 hen egg prophecy stands as Mary Bateman’s most ingenious and infamous exploit, embodying the essence of a chemical trick scam. Amid heightened religious tensions and global uncertainties like ongoing wars, Bateman announced that her ordinary hen was producing eggs inscribed with “Crist is coming”—a deliberate archaic spelling to enhance authenticity. Word spread rapidly through Leeds and beyond, drawing crowds eager to pay a penny for a glimpse of this divine omen, interpreted as a harbinger of the apocalypse.

The mechanics of this false prophecy hoax were elegantly simple, relying on basic chemistry and animal handling. Bateman used an acidic solution, typically vinegar, to etch messages onto eggshells invisibly. The acid reacted with the shell’s calcium carbonate, creating faint impressions that became visible after drying. She then carefully reinserted the treated eggs into the hen, ensuring the bird “laid” them naturally in front of witnesses. This apocalyptic hen trick not only generated substantial income—estimates suggest hundreds of visitors—but also amplified her status as a seer, with newspapers and pamphlets fueling the frenzy.

The scam’s success highlighted societal gullibility, where rational explanations were overshadowed by supernatural fervor. Skeptics eventually exposed the fraud by relocating the hen, which ceased producing inscribed eggs away from Bateman’s control. Yet, the episode’s ripple effects were profound, inspiring similar hoaxes and underscoring how misinformation can virally propagate. Analyzing this, one sees parallels in how absurd claims gain traction when tied to collective anxieties, offering a lesson in critically evaluating extraordinary assertions.

Crossing into Darkness: The Perigo Fraud and Fatal Consequences

Bateman’s deceptions took a tragic turn with William and Rebecca Perigo, a couple from Bramley seeking relief from Rebecca’s unexplained symptoms—flutters, visions, and distress—attributed to a curse. In 1806, Bateman, via her Mrs. Blythe alias, prescribed rituals involving sewn purses with coins and valuables for “safekeeping,” alongside consumables like pudding and honey. Unbeknownst to the Perigos, these were tainted with corrosive sublimate (mercuric chloride), a toxic substance causing excruciating symptoms.

Rebecca succumbed in 1807 after prolonged suffering, while William survived by halting the regimen. Bateman persisted in extracting payments from the widower, forging letters to maintain the illusion. Discovery came when William found the purses contained worthless items, prompting her 1808 arrest. A home search revealed poisons and stolen goods, linking her directly to the Bateman poison murder.

This case marked her shift from fraud to irreversible harm, driven by unchecked greed. It reveals how escalating cons can lead to unintended—or deliberate—tragedies, emphasizing the ethical boundaries manipulators often ignore.

Broader Suspicions: Additional Crimes and Patterns of Harm

Beyond the Perigos, Bateman was suspected in other incidents, including the 1803 deaths of two Quaker sisters and their mother in Leeds. As drapers, they sought her “medicines” for ailments, only to perish rapidly from what was deemed plague but later tied to poisoning. Bateman allegedly looted their shop post-mortem, evading justice due to rudimentary forensics.

Other yorkshire witch scams involved selling bogus cures, exploiting religious sects, and petty thefts. Her Southcottian ties provided a believer network, amplifying her reach. These patterns paint a portrait of habitual deception, where supernatural claims masked criminal intent, highlighting how such figures exploit trust vacuums.

The Reckoning: Trial, Verdict, and Aftermath

Bateman’s trial at York Assizes in March 1809 captivated the public, unfolding over a single day with overwhelming evidence: forgeries, poisons, and testimonies. Despite her denials and a feigned pregnancy plea, conviction for fraud and murder followed swiftly. Sentenced to execution and dissection, she spent her final days in York Castle, even conning fellow inmates with fortunes.

On March 20, 1809, amid a massive crowd, Bateman faced her end, proclaiming innocence. Her body, publicly dissected, became a macabre exhibit, with her skeleton preserved as a historical artifact. This closure reflected the era’s punitive spectacle, blending justice with curiosity.

Enduring Echoes: Cultural Resonance and Societal Reflections

Mary Bateman’s tale has inspired literature, folklore, and media, cementing her as the witch of Leeds. Her artifacts, like preserved remains, evoke ongoing fascination with criminal ingenuity.

Timeless Insights: Parallels and Preventive Wisdom

Bateman’s story mirrors contemporary deceptions, where illusions—chemical or digital—exploit fears. Key takeaways include:

- Cultivate skepticism: Demand evidence for miraculous claims.

- Recognize manipulation: Emotional appeals often signal fraud.

- Foster awareness: Education combats vulnerability.

By dissecting her methods, we gain tools to navigate modern pitfalls, transforming her legacy into a guide for discernment.

In essence, Mary Bateman’s journey from cunning fraudster to condemned figure illuminates deception’s allure and perils. As the definitive account of the Yorkshire Witch, this narrative equips readers with profound understanding, ensuring her history informs rather than haunts.