The Tuskegee Syphilis Study, also known as the Tuskegee Experiment, remains one of the most egregious ethical failures in U.S. medical history. From 1932 to 1972, the Public Health Service recruited 600 African American men in Macon County, Alabama, promising free healthcare for “bad blood” while deliberately withholding treatment—even after penicillin became widely available—to observe the untreated progression of syphilis. Rooted in racial bias, the study denied informed consent, caused preventable deaths and suffering, and harmed families through transmission. Exposed in 1972, it prompted public outrage, a multimillion-dollar settlement, landmark reforms like institutional review boards and the Belmont Report, and a 1997 presidential apology. The Tuskegee Syphilis legacy continues to shape health distrust in Black communities, contributing to lower participation in clinical trials and wider health disparities, while serving as a vital reminder of the need for transparency, equity, and unwavering ethical standards in medicine.

Long Version

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study: An Enduring Warning on Ethics and Equity in Medicine

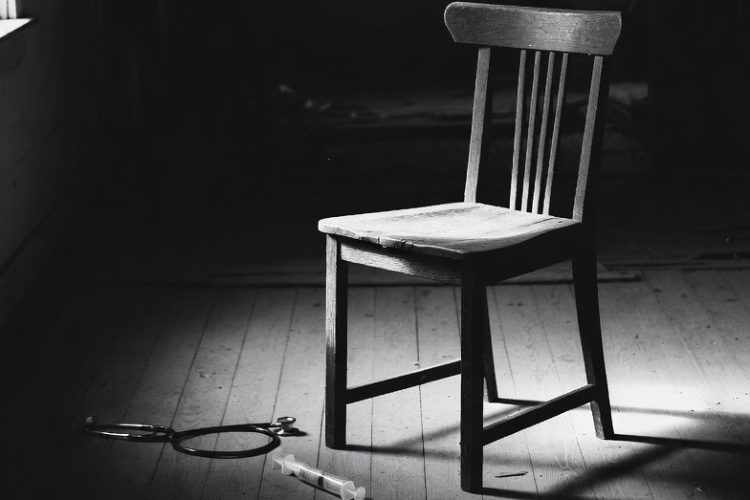

Picture this: In the grip of economic despair, hundreds of men are offered a lifeline—free healthcare, meals, and even burial support. But beneath this facade lies a calculated deception, where their bodies become unwitting vessels for scientific observation, denied life-saving treatment for decades. This is the grim essence of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, also known as the Tuskegee Experiment or the untreated syphilis study. Spanning 40 years, it remains a stark emblem of medical racism, ethical lapses, and the erosion of trust in healthcare systems. By examining its origins, methods, violations, revelations, and ripple effects, we uncover not just historical facts but profound lessons for fostering fairness and integrity in research today.

This in-depth exploration positions the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment as a pivotal case study in bioethics, revealing how systemic biases can undermine human rights. We’ll navigate its timeline, dissect the ethical breaches, trace the path to accountability, and reflect on its lasting influence on health disparities and public confidence. Through this lens, readers gain actionable insights to advocate for transparent, equitable medical practices.

Historical Foundations: The Context That Enabled the Study

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study emerged in 1932 against a backdrop of profound hardship and inequality in the American South. The Great Depression had ravaged rural communities, particularly in Macon County, Alabama, where poverty and limited access to healthcare were rampant. Syphilis, a sexually transmitted bacterial infection caused by Treponema pallidum, was prevalent in these areas, often going undiagnosed and untreated due to socioeconomic barriers.

Initiated by the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) in partnership with the Tuskegee Institute—a historically Black university—the study aimed to document the natural progression of untreated syphilis. Drawing inspiration from earlier observations like the Oslo Study in Norway, researchers sought to understand long-term effects on the body. They recruited 600 African American men, all aged 25 or older: 399 with latent syphilis and 201 uninfected as a control group. These participants, mostly sharecroppers with little formal education, were enticed with promises of treatment for “bad blood”—a colloquial term vaguely covering ailments like syphilis, anemia, or general malaise—along with free examinations, hot meals on visit days, and burial insurance.

However, the Tuskegee medical experiment was steeped in Tuskegee racism in medicine from the start. Prevailing pseudoscientific notions suggested racial differences in disease susceptibility and progression, justifying the selection of Black men as subjects. No women were included, though the study’s repercussions extended to them indirectly through transmission. This setup exploited vulnerabilities, prioritizing data over dignity and foreshadowing the ethical quagmire to come.

The Unfolding Process: A Chronicle of Withheld Care

The Tuskegee Syphilis timeline reveals a methodical pattern of observation and omission over four decades. From 1932 onward, participants underwent regular assessments, including blood tests, X-rays, and invasive lumbar punctures—euphemistically called “spinal shots”—to track syphilis’s impact on organs, nerves, and overall health. Symptoms progressed unchecked: initial skin rashes gave way to cardiovascular issues, neurological damage, blindness, insanity, and organ failure.

In the early phases, treatments were rudimentary and ineffective, consisting of mercury or arsenic-based remedies that offered little benefit. But a turning point arrived in the 1940s with penicillin’s discovery as a safe, effective antibiotic for syphilis. By 1943, it was the standard treatment, and by 1947, it was widely accessible. Yet, PHS officials deliberately withheld it, citing the need to preserve the study’s integrity for observing the disease’s full course. Participants received placebos like aspirin or iron tonics to sustain the illusion of care.

This denial extended to active interference: During World War II, researchers ensured draft boards did not treat participants during mandatory physicals. By the 1950s, the experiment had become an institutional fixture, with findings published in medical journals while ignoring the human toll. Approximately 128 men died from syphilis or its complications, with many more enduring lifelong suffering. Families were collateral victims—wives contracted the infection, and at least 19 children were born with congenital syphilis.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment’s execution embodied a chilling detachment, where scientific curiosity trumped compassion. It wasn’t mere oversight but a structured system of deception, underscoring how power imbalances in healthcare can perpetuate harm.

Core Ethical Breaches: Dissecting the Moral Failures

The Tuskegee ethical issues cut to the heart of medical principles, exposing violations that shocked the world. Central was the absence of informed consent: Participants were never told their diagnosis, the study’s true aim, or the risks. This stripped them of autonomy, a fundamental right in ethical research.

Other key infractions included:

- Non-Maleficence Violation: The deliberate withholding of penicillin post-1940s caused preventable pain and death, breaching the “do no harm” oath.

- Justice Denied: Targeting impoverished Black men reflected Tuskegee racism in medicine, exploiting a marginalized group under the guise of science. It echoed eugenics-era beliefs that devalued certain lives.

- Beneficence Ignored: Instead of promoting well-being, the study prioritized data, offering superficial incentives while inflicting harm.

- Deception as Policy: Misinformation about “bad blood” treatment maintained compliance, with burial stipends ensuring post-mortem autopsies for more data.

- Institutional Complicity: Multiple generations of researchers sustained the study, despite internal ethical concerns, highlighting conflicts between advancement and humanity.

Comparatively, the Tuskegee Syphilis Study paralleled other dark chapters, such as the Guatemala syphilis experiments where subjects were intentionally infected, or even Nazi medical trials that prompted the Nuremberg Code in 1947—ironically, during the study’s ongoing run. These breaches not only harmed individuals but eroded the ethical fabric of medicine, demanding systemic reform.

Revelation and Reckoning: Pathways to Justice

The study’s exposure in 1972 marked a watershed moment. Whistleblower Peter Buxtun, a PHS investigator, had raised alarms since the 1960s, but it took his leaks to the Associated Press for journalist Jean Heller’s article to ignite public fury. Revelations detailed the deception, prompting congressional hearings under Senator Edward Kennedy.

Immediate actions followed:

- An Ad Hoc Advisory Panel deemed the study “ethically unjustified,” recommending its termination in October 1972.

- A 1973 class-action lawsuit, Pollard v. United States, secured a $10 million settlement in 1974, distributing funds to Tuskegee Syphilis victims, survivors, and heirs.

- Legislative reforms included the National Research Act of 1974, establishing institutional review boards (IRBs) to safeguard participants through rigorous oversight.

- The Belmont Report of 1979 codified core principles: respect for persons, beneficence, and justice, directly countering Tuskegee’s flaws.

In 1997, President Bill Clinton issued a formal Tuskegee apology, acknowledging governmental wrongdoing and establishing the Tuskegee University National Center for Bioethics in Research and Health Care. The Tuskegee Health Benefit Program provided lifetime medical care to survivors and families, later expanded to include descendants. These steps, while reparative, sparked ongoing debates about adequate compensation and broader racial justice in health.

Enduring Impacts: Shaping Contemporary Healthcare Dynamics

The Tuskegee Syphilis legacy permeates modern medicine, fueling Tuskegee health distrust particularly among Black communities. Surveys indicate high awareness—over 80% among African Americans—correlating with reduced trust in researchers and lower participation in clinical trials. This underrepresentation hampers progress on conditions disproportionately affecting minorities, like hypertension or diabetes.

Manifestations include:

- Vaccine and Treatment Hesitancy: Historical echoes contribute to skepticism during health crises, from HIV initiatives to broader immunization efforts, though multifaceted factors like access play roles.

- Health Disparities: Studies link the legacy to widened racial gaps in life expectancy and care-seeking behaviors, with mistrust accounting for delayed diagnoses and poorer outcomes.

- Systemic Reforms: It catalyzed diversity requirements in research and community engagement protocols, ensuring inclusive designs.

- Broader Societal Reflections: The study informs discussions on medical exploitation, from pharmaceutical pricing inequities to biases in emerging technologies like AI-driven diagnostics, where algorithms might replicate historical prejudices if not carefully vetted.

In essence, the Tuskegee Syphilis victims’ suffering catalyzed a paradigm shift, emphasizing equity as essential to sustainable health advancements. It reminds us that ethical lapses have intergenerational costs, urging vigilance in all medical endeavors.

Actionable Insights: Applying Lessons to Prevent Recurrence

Distilling the Tuskegee Experiment’s teachings yields practical strategies for individuals, professionals, and policymakers:

- Champion Informed Consent: Always ensure clear, comprehensive communication in any health interaction.

- Challenge Biases: Educate on recognizing and addressing racial prejudices in training and protocols.

- Promote Transparency: Build trust through open dialogues and community involvement in research planning.

- Advocate for Inclusivity: Support initiatives that diversify trials and address barriers to care.

- Remember and Educate: Integrate this history into curricula to foster ethical awareness and empathy.

By internalizing these, we honor the past while fortifying the future against similar injustices.

Final Reflections: Building Trust Through Remembrance

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study encapsulates a tragic intersection of science, racism, and ethics, where pursuit of knowledge inflicted irreparable harm. From its deceptive recruitment to the withheld cures and eventual reckoning, it exposed vulnerabilities that reforms have sought to mend. Yet, its shadow endures, influencing how we approach health equity and innovation. Embracing this history empowers us to demand accountability, ensuring medicine serves all with dignity and justice. In remembering the Tuskegee Syphilis victims, we commit to a legacy of healing, not harm—one that prioritizes humanity above all.