A new study shows nearly 70% of U.S. adults could be obese under a redefined framework that uses waist size, body fat, and BMI, compared to 43% with BMI alone. Traditional BMI misses hidden obesity risks, like belly fat, which increases chances of diabetes, heart disease, and death, even in normal-weight people. The new approach uses waist circumference and body fat measures to better spot health risks from visceral fat. This shift highlights the obesity epidemic’s scale, affecting older adults most. Antiobesity drugs and lifestyle changes can help, but the new definition may expand treatment access. It’s a smarter way to identify and manage obesity risks.

Long Version

Redefining Obesity: The Shift from BMI to a More Accurate Assessment of Health Risks

In the midst of an escalating obesity epidemic, a groundbreaking study has revealed that nearly 70% of U.S. adults could be classified as obese under a proposed new obesity framework that incorporates waist circumference, body fat measures, and other anthropometric data alongside traditional body mass index (BMI). This paradigm shift in obesity conceptualization highlights how relying solely on BMI may significantly underestimate true obesity risk, particularly in individuals with normal weight but excess fat distribution, often referred to as hidden obesity or belly fat obesity.

The study, drawing from a large-scale, population-based study involving over 300,000 participants, analyzed electronic health record (EHR) data and longitudinal cohort study results to assess obesity prevalence. Under the conventional BMI-based definition, where obesity is indicated by a BMI of 30 or higher, about 42.9% of adults qualify. However, the new approach boosts this figure to 68.6%, marking a dramatic obesity prevalence increase. This adjustment accounts for adiposity, excess fat, and fat distribution, revealing that many people previously categorized as overweight or normal weight actually harbor significant health risks due to central adiposity and visceral adiposity.

The Limitations of Traditional BMI in Obesity Classification

Body mass index, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared, has long been the cornerstone of obesity classification. It categorizes individuals into ranges: underweight (below 18.5), normal weight (18.5-24.9), overweight (25-29.9), and obese (30 or higher, with subclasses like Class I, II, and III obesity). While BMI is simple and cost-effective, its flaws are well-documented. It fails to distinguish between body fat and muscle mass, often misclassifying muscular individuals as obese or overlooking those with high body fat percentages but lower overall weight.

Moreover, BMI does not capture body composition or fat distribution, key factors in metabolic health. For instance, abdominal fat—particularly intra-abdominal fat—poses greater threats than subcutaneous fat elsewhere on the body. This oversight can lead to underestimation of risks in people with normal BMI but elevated anthropometrics, such as those with metabolic dysfunction or cardiometabolic disease. Critics argue that BMI’s one-size-fits-all approach ignores race-specific BMI cutoffs and sex-specific thresholds, further compounding inaccuracies.

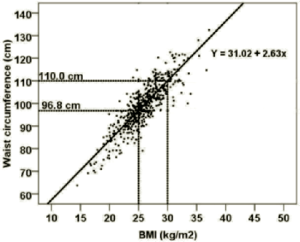

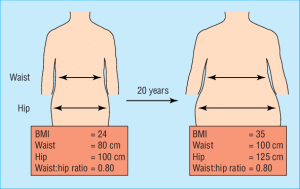

To illustrate these limitations, consider diagrams that correlate BMI with measures like waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), showing how BMI alone can mislead.

The New Obesity Framework: Integrating Anthropometric Measures

A comprehensive obesity framework has been proposed that redefines the condition as excess adiposity, with or without abnormal fat distribution or function, leading to organ dysfunction or physical impairment. This moves beyond BMI to include direct measures of body fat, such as dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scans for precise body fat assessment, though simpler anthropometric measures like waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), and waist-to-height ratio are prioritized for practicality.

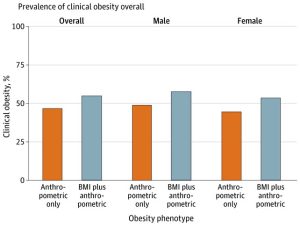

Under this obesity classification, individuals are labeled obese if they exhibit BMI-plus-anthropometric obesity (high BMI plus at least one elevated anthropometric measure) or anthropometric-only obesity (normal BMI but two or more elevated anthropometrics). The framework also distinguishes between preclinical obesity—where excess fat increases health risks without current illness—and clinical obesity, characterized by obesity-associated organ dysfunction, such as cardiovascular events, incident diabetes, or metabolic syndrome.

This approach acknowledges obesity phenotypes, including variations in visceral adiposity and intra-abdominal fat, which are linked to higher odds ratios (ORs) and adjusted hazard ratios (AHRs) for adverse outcomes. For example, central adiposity elevates risks for diabetes, hypertension, and all-cause mortality, even in those with seemingly healthy BMIs.

Key Findings from the Study

Leveraging a large cohort, the study applied this new definition to reveal stark insights. Obesity prevalence surged to 68.6%, with the increase driven by those with anthropometric-only obesity—individuals overlooked by BMI alone but facing elevated risks for cardiometabolic disease, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and mortality. Notably, about 36.1% of the cohort had clinical obesity, rising with age to nearly 80% in those over 70.

Prevalence varied by demographics: higher in females for some measures, and influenced by race and sex-specific factors. The study used International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes to track outcomes, showing that hidden obesity contributes to metabolic dysfunction and physical impairment.

Visualizing this shift, charts depict the dramatic rise in classified cases under the new criteria.

Health Risks and Implications of Central and Visceral Adiposity

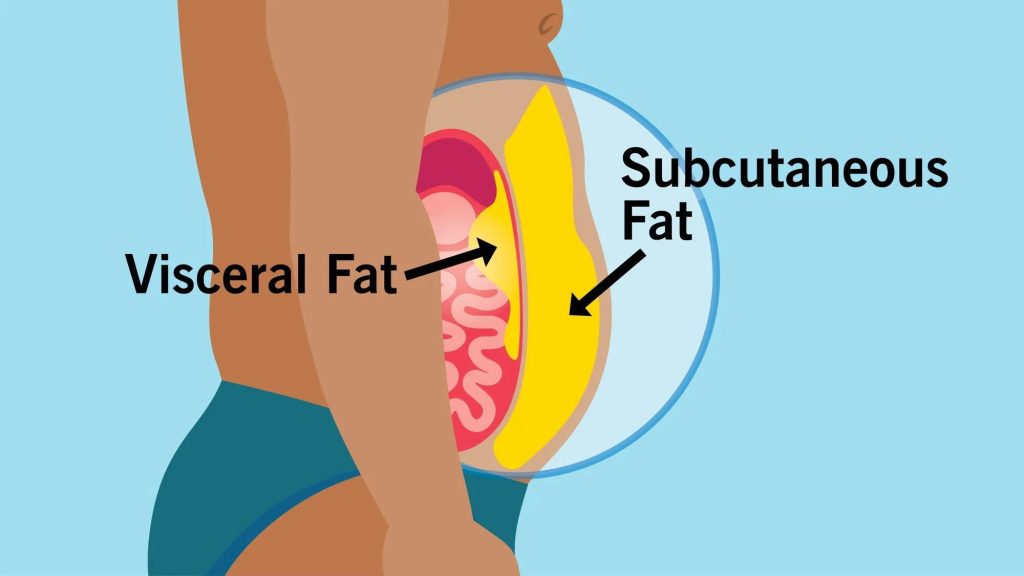

The core concern with the new definition is its focus on health risks tied to fat distribution. Visceral adiposity, the fat surrounding internal organs, is particularly insidious, promoting inflammation and insulin resistance. Unlike subcutaneous fat, which is less harmful, excess visceral fat heightens risks for cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, stroke, and even colorectal issues. Studies show a J-shaped association between waist circumference and all-cause mortality, underscoring the dangers of belly fat obesity.

Illustrations clarify the distinction: visceral fat encases organs, driving metabolic health decline, while subcutaneous fat lies under the skin with fewer immediate threats.

This refined view reveals that even normal-weight individuals with elevated anthropometrics face higher incident diabetes and cardiovascular events, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions.

Broader Context: Addressing the Obesity Epidemic and Treatment Options

The obesity epidemic in the U.S. is projected to affect nearly half the population by 2030 under traditional metrics, but the new framework suggests an even more urgent crisis. Factors like sedentary lifestyles and poor diet exacerbate excess fat accumulation, leading to widespread metabolic dysfunction.

Treatment has evolved with antiobesity medications, including glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP1RAs) like semaglutide, which target adiposity and improve cardiometabolic outcomes. Lifestyle changes remain foundational, but the new classification could expand access to these therapies for those with preclinical obesity, potentially reducing long-term mortality and organ dysfunction.

A Path Forward: Valuable Insights for Better Health Management

This update represents a paradigm shift in obesity conceptualization, offering a more nuanced, authoritative tool for clinicians and individuals alike. By integrating anthropometric measures with BMI, we can better identify at-risk populations, prevent hidden obesity from escalating into clinical obesity, and mitigate associated health risks. As research continues, including updates through 2025, this framework promises to enhance metabolic health outcomes and combat the obesity epidemic more effectively.