High-conflict homes with chronic yelling, family violence, emotional or physical abuse create ongoing stress for children, reshaping their developing brains. This early adversity heightens activity in the amygdala and anterior insula—key areas for threat detection—producing patterns similar to those seen in combat veterans. Children become hypervigilant, staying in a constant state of hyperarousal that raises risks for anxiety, depression, PTSD-like symptoms, and long-term mental health issues. Brain changes include stronger salience network connections, reduced prefrontal control over emotions, attentional bias toward threats, and structural differences like smaller hippocampal volume. These effects can lead to cognitive deficits, social challenges, and difficulties in adulthood. However, supportive caregiving, positive parenting, early interventions, and building resilience through secure relationships and skill-building programs can buffer the impact, promote healthier brain development, and help break cycles of trauma.

Long Version

The Hidden Toll: How High-Conflict Homes Reshape Children’s Brains and Futures

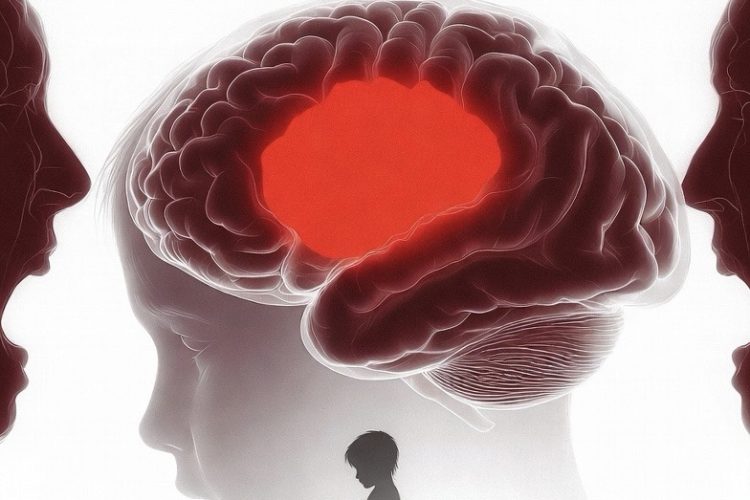

In homes marked by chronic yelling, family violence, and persistent emotional abuse, children endure a form of early life adversity that extends far beyond immediate distress. This chronic stress, often stemming from physical abuse, domestic violence, or unrelenting conflict, triggers profound changes in brain development, fostering heightened vigilance and threat hypersensitivity. Studies reveal that violence-exposed youth exhibit neural patterns mirroring those in combat soldiers, with hyper-reactive amygdala and anterior insula activation during threat detection. These alterations in the fear neurocircuitry can lead to persistent hyperarousal, increasing risks for anxiety disorders, depression, and PTSD-like symptoms, while underscoring the urgency of addressing adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) to mitigate long-term psychopathology.

Unraveling the Neurobiological Impacts

At the core of these changes lies the brain’s response to trauma exposure. The amygdala, a key player in emotional processing and fear system activation, becomes hyper-reactive in maltreated children, showing bilateral activation and heightened neural response to threat cues like angry faces or fearful faces. This amygdala activation is often coupled with increased activity in the anterior insula, particularly the right fronto-insular cortex (rFIC), which processes socioemotional deficits and salience detection. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies demonstrate that such brain activity patterns result from excitotoxic effects and cortisol secretion dysregulation, leading to neural adaptations that prioritize threat detection over neutral stimuli.

The salience network (SN), involving the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) and fronto-insular responses, plays a pivotal role in this hypersensitivity. In violence-exposed youth, intrinsic connectivity within the SN strengthens, enhancing conflict interference and pre-attentive emotional processing, while disrupting the default mode network (DMN) responsible for introspection and emotional response inhibition. Connectivity alterations, such as reduced amygdala-vmPFC connectivity and hippocampus-vmPFC connectivity, further impair emotional valence regulation and attentional bias, making everyday interactions feel like potential dangers. These changes also affect amygdala-brainstem connectivity, promoting sensitization rather than habituation to stressors, and can manifest in cognitive deficits like slower reaction times in tasks such as the Go/NoGo task or dot-probe paradigm.

Broader brain regions, including the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and hippocampus, suffer from these early insults. Chronic stress from child maltreatment leads to structural abnormalities, such as reduced hippocampal volume, which correlates with memory impairments and increased vulnerability to psychiatric disorders. Blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) contrast in fMRI scans highlights these shifts, showing latent neural risk markers that predict future mental health challenges. Over time, these adaptations can exacerbate neural circuit organization, creating a feedback loop where minor stressors trigger disproportionate responses, further entrenching patterns of hypervigilance.

Psychological and Behavioral Consequences

The rewiring of developing brains in high-conflict environments fosters a state of hypervigilance and hyperarousal, where children remain in a constant “fight or flight” mode. This mirrors PTSD symptoms seen in adults, including nightmares, separation anxiety, and intrusive thoughts, but in youth, it often presents as behavioral issues captured by tools like the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) or Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children (TSCC-A). Anxiety disorders emerge from this threat hypersensitivity, with children displaying exaggerated responses to neutral faces or masked faces in experimental paradigms. This heightened state can interfere with academic performance, as attentional bias diverts focus from learning to scanning for threats.

Depression risks escalate as well, linked to prodromal indicators like mood dysregulation assessed via the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ). Event-related potential (ERP) studies reveal that trauma-exposed children experience heightened neural reactivity, contributing to affect processing difficulties and increased stress generation over time. Socioemotional deficits, such as poor emotional valence interpretation, can lead to interpersonal challenges, exacerbating isolation and perpetuating cycles of psychopathology. In adolescence, these effects may manifest as risk-taking behaviors or withdrawal, complicating social development and peer relationships.

Long-term, these effects compound into adult mental health issues. Childhood trauma subtypes, including emotional abuse, correlate with abnormal brain connectivity in major depressive disorder (MDD), heightening risks for chronic anxiety and depression. Tools like the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIT) and UCLA PTSD Reaction Index quantify these symptoms, showing elevated scores in violence-exposed groups. Behavioral Assessment System for Children (BASC) evaluations further highlight cognitive deficits, such as impaired executive function, stemming from disrupted neural circuit organization. Without intervention, these patterns can influence decision-making, empathy, and emotional regulation well into adulthood, potentially leading to relational difficulties or occupational challenges.

Evidence from Neuroimaging and Longitudinal Studies

Pioneering fMRI evidence illustrates that maltreated children display amygdala and anterior insula hyperactivity akin to combat veterans when viewing angry faces, indicating shared mechanisms in threat processing. Subsequent research expands on this: analyses of adversity exposure found altered brain reactivity in adults, tracing back to childhood trauma’s impact on resting-state functional connectivity. Longitudinal studies reveal that early violence exposure predicts decreased connectivity within the salience network and aberrant social processes, with dynamic alterations in aversive learning networks.

Recent investigations confirm detrimental impacts on depression and anxiety behaviors through brain function changes. Analyses link violence exposure to adolescent neural network density, emphasizing the role of threat cues in reshaping connectivity. Instruments like the Violence Exposure Scale for Children-Revised (VEX-R) and Traumatic Events Screening Inventory (TESI) help quantify exposure, correlating it with heightened amygdala responses dependent on caregiver factors. These findings highlight how cumulative exposure intensifies neural changes, with dose-dependent effects where more frequent conflict leads to more pronounced alterations.

Long-Term Implications and Societal Ramifications

Beyond childhood, these neural adaptations persist, influencing career success and interpersonal relationships. Altered hippocampus, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex functions due to HPA axis dysregulation can lead to excitotoxic effects, manifesting in adulthood as increased vulnerability to stress-related disorders. Structural and functional brain abnormalities from prolonged stressor exposure underscore the need for early intervention to prevent intergenerational transmission of trauma. On a broader scale, this contributes to societal burdens, including higher healthcare costs, reduced productivity, and perpetuation of cycles in families and communities, emphasizing the public health imperative to support at-risk households.

Building Resilience: Interventions and Protective Factors

Fortunately, resilience can be cultivated through targeted strategies. Maternal buffering, where supportive caregiving mitigates stress impacts, promotes positive neural adaptations and emotional regulation. Programs focused on building healthy children offer preventive interventions for high-risk families, emphasizing positive parenting and mental health support over multiple sessions. Active skill-building, such as child-led play and nurturing relationships, strengthens protective factors against ACEs, helping to rewire neural pathways toward adaptability.

Community-based approaches, including caregiver support interventions for conflict-affected parents, emphasize group sessions to enhance resilience factors. Pediatric guidelines advocate partnering with families to prevent toxic stress, promoting developmentally appropriate play and therapeutic alliances. Social connections and parental resilience, as outlined in established frameworks, buffer stressors and foster secure attachments. Additional strategies, like mindfulness training or trauma-informed therapy, can facilitate habituation to stressors, reducing sensitization and improving overall mental health outcomes. By integrating these elements early, it’s possible to interrupt the cycle of hyperarousal and promote long-term well-being.

In summary, high-conflict homes impose a heavy burden on children’s brains, driving hyper-reactive responses and mental health risks through intricate neural mechanisms. Yet, with evidence-based interventions and resilience-building, these trajectories can shift toward healthier outcomes, offering hope for affected youth and a pathway to breaking generational patterns.