Negative numbers evolved from practical needs like tracking debts in ancient China and India. Chinese scholars used red and black rods to show positive and negative amounts, while Indian mathematicians such as Brahmagupta defined clear sign rules and allowed negative solutions in equations. Islamic mathematicians expanded these ideas in algebra and commerce, influencing Europe through translations. Europeans resisted negatives for centuries, calling them absurd, until the 17th century, when the number line and new algebraic methods made them widely accepted. Today, negative numbers are essential in science, finance, engineering, and everyday problem-solving.

Long Version

The Evolution of Negative Numbers: From Ancient Debts to Modern Mathematics

In the vast tapestry of the history of mathematics, few concepts have sparked as much debate and gradual acceptance as negative numbers. These entities, once dismissed as impossible or absurd, now form the backbone of arithmetic operations, algebraic concepts, and number systems worldwide. Their journey reflects the interplay between practical needs—like bookkeeping and accounting—and theoretical advancements in quadratic equations and beyond. This article traces their origins, rejections, and eventual embrace, highlighting key milestones in ancient mathematics, medieval mathematics, and beyond.

Ancient Foundations in China and India

The roots of negative numbers stretch back to ancient civilizations, where they emerged from real-world necessities such as tracking debts and fortunes. In Chinese numeration, evidence of negative quantities appears as early as the Han Dynasty around 200 BCE. The seminal text Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art, compiled during this period, introduced a sophisticated rod system for calculations. This involved red rods for positive numbers (representing assets or gains) and black rods for negative numbers (symbolizing deficits or debts). Commentators like Liu Hui in the 3rd century CE refined these methods, allowing for operations such as subtracting same-signed numbers or adding differently signed numbers. The system even handled signed zero implicitly, through the cancellation of opposing rods, demonstrating an early grasp of opposite senses in quantities. This approach was practical for solving systems of linear equations and financial problems, showing how negatives arose from everyday commerce and administration.

Meanwhile, in 7th-century India, the mathematician Brahmagupta provided the most explicit framework for negative numbers in his treatise Brahma-Sphuta-Siddhanta (AD 628). As a scholar, Brahmagupta described affirmative quantities as positives (fortunes) and debts as negatives, establishing clear rules of signs for arithmetic operations. For instance, he noted that the product of two negatives yields a positive, a rule that anticipated modern algebra. His work extended to quadratic equations, where he accepted negative roots, and even touched on zero and negatives, defining operations like division by zero in limited contexts. The Bakhshali Manuscript, an earlier Indian artifact dating back to around the 3rd or 4th century CE, also hints at similar ideas through its use of a dot for zero and notations for subtraction that implied negatives, underscoring India’s pivotal role in ancient mathematics.

These developments were not isolated; they influenced Islamic mathematics through translations, such as during the Abbasid era when scholars in Baghdad accessed Indian texts, fostering cross-cultural exchanges that enriched algebraic knowledge.

Transmission and Refinement in Islamic Mathematics

Islamic scholars built upon Indian and Chinese foundations, integrating negative numbers into broader algebraic concepts. Al-Khwarizmi, in his 9th-century work Al-jabr wa’l-muqabala, focused on balancing equations but notably avoided negative coefficients, adhering to positive quantities for geometric proofs to maintain tangible interpretations. However, later figures like Abū al-Wafā’ al-Būzjānī in the 10th century treated debts as negatives in practical contexts for scribes and businessmen, applying them in calculations for inheritance and commerce. By the 12th century, Al-Samaw’al advanced polynomial divisions and rules for signs, stating that negatives must be counted as terms in expansions. Al-Karaji further explored coefficients, using negatives in equations, though acceptance remained cautious amid debates over their philosophical validity.

This era bridged influences from Hellenistic Greece, where earlier mathematicians like Diophantus in the 3rd century CE had rejected negative solutions as absurd in his Arithmetica, preferring to reframe problems to yield only positive results. Islamic mathematicians, however, applied negatives in trade and astronomy, laying groundwork for European exposure through translations and scholarly networks.

European Skepticism and Medieval Resistance

Despite these advancements, European skepticism toward negative numbers persisted for centuries. In medieval mathematics, figures like Fibonacci in his Liber Abaci (1202) allowed negatives for debts in financial problems but rejected them in other contexts, viewing them as losses rather than true numbers. Bhāskara II, an Indian contemporary in the 12th century, similarly dismissed negative roots as inadequate for geometric interpretations, echoing broader rejection of negatives in favor of positive solutions.

The Renaissance brought tentative exploration. Nicolas Chuquet in the 15th century and Michael Stifel in the 16th century experimented with negatives in algebraic notations, but Gerolamo Cardano in Ars Magna (1545) labeled them fictitious numbers, struggling with their meaning in cubic equations. Absurd equations yielding negatives were often discarded, reflecting a view that positives alone sufficed for real-world applications, with negatives seen as mere artifacts of manipulation.

The Turning Point: 17th-Century Acceptance in Europe

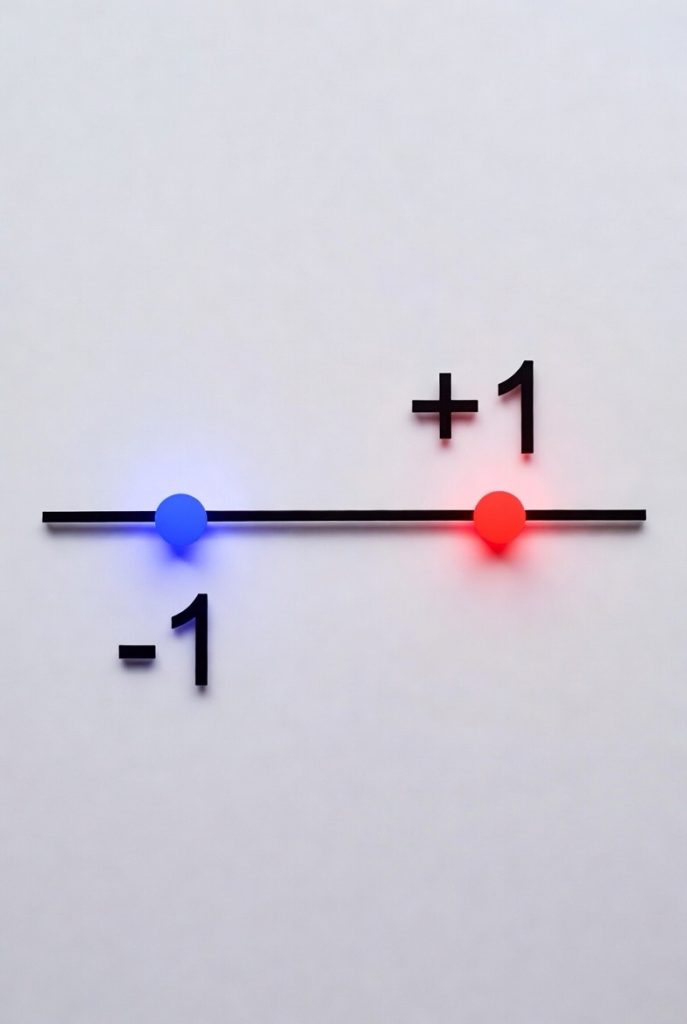

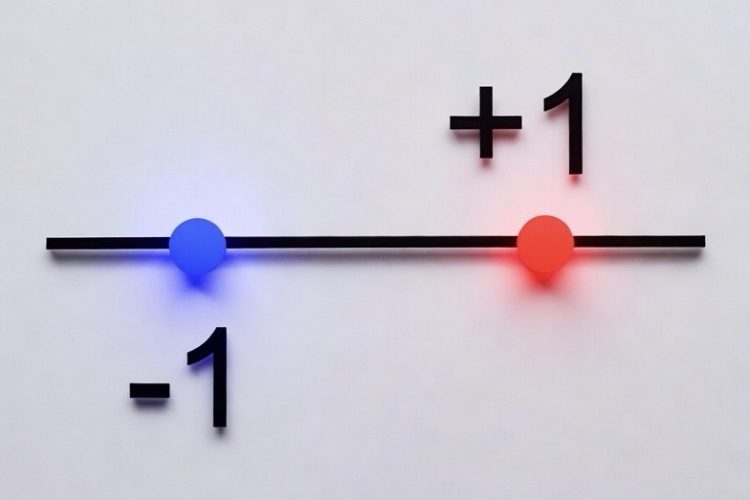

The 17th century marked an explosion in accepting negatives across Europe, driven by algebra and accounting’s practical value. John Wallis pioneered the number line in 1657, visualizing negatives as extensions to the left of zero, providing a geometric interpretation that made them more intuitive. He argued negatives were larger than infinity in a certain sense yet less than zero, sparking philosophical debates but helping to demystify their nature.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Johann Bernoulli, Leonhard Euler, and Jean le Rond d’Alembert engaged in controversies over logarithms of negatives, questioning if log(-x) equaled log(x) or required complex numbers. Leibniz initially saw them as imaginary or non-existent, while Euler’s work on complex numbers in the 18th century resolved some issues, affirming negatives’ utility in analysis. Caspar Wessel and Jean-Robert Argand later contributed to graphical representations of complex numbers, and William Rowan Hamilton extended ideas to quaternions in the 19th century.

Critics like Francis Maseres and William Frend resisted into the 18th century, calling negatives illogical and advocating for positive-only mathematics, but Augustus De Morgan and George Peacock formalized their logical foundations in the 19th century, investigating arithmetic laws and abstract algebra. This era solidified negatives in sign rules, square roots of negatives (leading to imaginary numbers), and broader mathematical acceptance, paving the way for fields like vector analysis and coordinate geometry.

Broader Impacts and Legacy

Throughout history, negatives addressed debts as negative assets, enabling sophisticated bookkeeping and accounting. From Chinese rod systems to Indian quadratic formulas, they facilitated arithmetic operations like adding positives and negatives or handling negative roots. In Europe, their integration into number systems resolved absurd numbers, transforming algebraic concepts and allowing for the development of calculus and physics.

Today, negatives are indispensable in fields from physics (representing forces in opposite directions or subzero temperatures) to finance (modeling losses and liabilities), computer science (in algorithms and data structures), and engineering (in control systems and electrical circuits). Their story—from rejection as absurd entities to essential tools—illustrates mathematics’ evolution, blending cultural exchanges, practical innovations, and intellectual perseverance across civilizations.

This comprehensive exploration reveals how negative numbers, once peripheral, became central to our understanding of quantity and balance, offering timeless insights into human ingenuity and the power of abstract thinking.