Day of the Dead (Día de los Muertos) is a Mexican holiday honoring deceased loved ones with joy, not mourning. Celebrated November 1–2, it blends Aztec and Maya traditions with Catholic All Saints’ and All Souls’ Days. Families build ofrendas—altars with photos, pan de muerto, cempasúchil marigolds, sugar skulls (calaveras), and favorite foods like tamales and mole—to welcome spirits home. Symbols include La Catrina, papel picado, and calacas (skeletons). Key rituals: cleaning graves, night vigils, literary calaveras (satirical poems), and parades. Regional styles vary—Hanal Pixan in Yucatán, giant kites in Guatemala. UNESCO-listed since 2008, it celebrates life, family, and cultural identity through food, art, and community.

Long Version

Day of the Dead

The Day of the Dead, known in Spanish as Día de los Muertos or Día de Muertos, is a vibrant holiday and celebration rooted in Mexico’s rich cultural heritage. This multi-day festival honors ancestors and the deceased, blending remembrance with joyful community gatherings that affirm the continuity between life and death. Observed primarily on November 1 and 2, it coincides with the Roman Catholic observances of All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day, reflecting a profound syncretism of indigenous traditions and colonial influences. Families come together to welcome the spirits and souls of their loved ones, creating an atmosphere of festivity rather than mourning. Recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2008, the Day of the Dead has evolved into a global phenomenon, influencing parades, art, and media while preserving its core emphasis on family bonds and cultural identity.

History and Origins

The origins of the Day of the Dead trace back over 3,000 years to pre-Columbian indigenous civilizations, particularly the Aztec and Maya peoples. In Aztec culture, death was viewed not as an end but as a phase in the eternal cycle of existence, with elaborate rituals dedicated to the underworld realm of Mictlán, ruled by the deities Mictlantecuhtli, the lord of the dead, and Mictecacíhuatl, the lady of the dead. The Aztecs held festivals like Quecholli, honoring the war god Mixcóatl with offerings near graves, including tamales for the deceased. Similarly, the Maya celebrated death through rites that emphasized ancestral veneration, laying the groundwork for modern customs.

With the arrival of Spanish conquistadors in the 16th century, these indigenous practices underwent syncretism with Roman Catholic traditions introduced during colonization. The Catholic Church aligned the native observances with All Saints’ Day on November 1, dedicated to the angelitos or spirits of deceased children, and All Souls’ Day on November 2, focused on adult souls. This fusion was further shaped during Mexico’s post-independence era, particularly under President Lázaro Cárdenas in the 20th century, who promoted indigenismo to foster national identity by emphasizing Aztec and Maya roots while diminishing overt religious elements. Some scholars argue that the holiday as known today emerged more from medieval European customs adapted in the colonial period, evolving into a distinctly Mexican festival through cultural resistance and adaptation.

The holiday gained international recognition when UNESCO inscribed the “Indigenous festivity dedicated to the dead” on its Representative List in 2008, highlighting its role in preserving Mexico’s cultural diversity and promoting dialogue between the living and the deceased. Over time, this recognition has helped integrate the celebration into broader discussions on cultural preservation, encouraging educational programs and international exchanges that deepen global understanding of Mexican heritage.

Beliefs and Customs

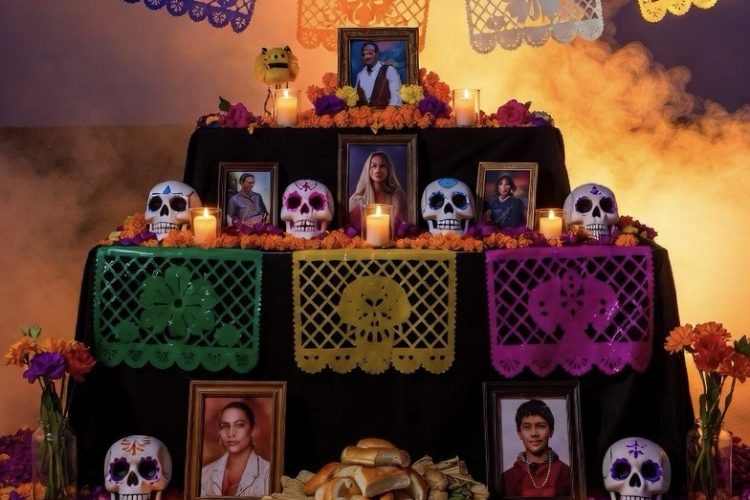

At its heart, the Day of the Dead is a celebration of life through remembrance, where death is treated familiarly and without fear. Families believe that the spirits of the deceased return annually to reunite with the living, guided by rituals that invite their presence. Central to this is the construction of ofrendas, elaborate home altars or offerings adorned with photos, memorabilia, and the deceased’s favorite items to honor their memory and facilitate their journey from the afterlife. These altars often incorporate elements representing the four classical elements—earth, wind, fire, and water—to symbolize balance and the interconnectedness of existence.

Customs include cleaning and decorating gravesites, holding all-night vigils with picnics, and sharing stories or humorous anecdotes about the departed. Children often participate in calaverita, collecting candies or small gifts, while literary calaveras—satirical rhyming verses mocking death or the living—add a playful, irreverent tone. These practices underscore the holiday’s emphasis on community and family, transforming mourning into a festive reaffirmation of enduring bonds. In many regions, music and dance play key roles, with mariachi bands or traditional folk tunes enhancing the communal spirit and helping to bridge generations through shared cultural expressions.

Symbols and Decorations

The Day of the Dead is renowned for its vivid symbols that blend indigenous iconography with artistic expressions. Calaveras, or skulls, and calacas, skeleton figures, represent the vitality of life amid death, often crafted as sugar skulls inscribed with names and given as gifts to both the living and the dead. The iconic La Calavera Catrina, a skeletal lady in elegant attire created by artist José Guadalupe Posada as a social critique of 19th-century Mexican aristocracy, was later popularized by Diego Rivera and has become a nationalist emblem, frequently featured in parades and costumes. This figure embodies the holiday’s satirical edge, reminding participants of death’s equality across social classes.

Bright cempasúchil marigold flowers, known for their pungent scent and golden petals, are scattered to guide souls home, forming paths or adorning ofrendas. Papel picado, intricately cut-paper decorations, flutter in the wind, symbolizing the fragility of life. Alfeñiques, molded sugar paste figures, and tapetes de arena, colorful sand carpets depicting scenes of the afterlife, add layers of artistry to altars and streets. In some regions, shells sewn into clothing are used in dances to “awaken” the dead, while comparsas, lively processions or masquerades, bring communities together in spirited displays. Additional symbols like candles represent light guiding the way, incense purifies the air, and salt wards off evil, each contributing to a multisensory experience that engages sight, smell, and sound.

Foods and Beverages

Culinary traditions are integral to the Day of the Dead, with offerings on ofrendas including the deceased’s preferred dishes to nourish their spirits. Pan de muerto, a sweet bread shaped like bones or skulls and dusted with sugar, is a staple, symbolizing the cycle of life. Tamales, steamed corn dough parcels filled with meats or vegetables, and mole, a complex sauce blending chilies and chocolate, are commonly prepared for family feasts. These foods not only honor the dead but also foster family unity, as recipes are passed down through generations, often with variations reflecting personal or regional tastes.

Beverages like atole, a warm corn-based drink, and champurrado, its chocolate-infused variant, provide comfort during vigils. Alcoholic spirits such as mezcal, an agave distillate, and pulque, a fermented agave sap, are offered to adult souls, alongside candied pumpkin and other sweets. In Maya-influenced areas, mukbil pollo, a Yucatecan buried chicken dish baked underground, highlights regional flavors. The preparation and sharing of these items emphasize abundance and hospitality, ensuring the spirits feel welcomed and sated, while also serving as a means to educate younger family members about cultural continuity.

Observances in Mexico

In Mexico, the holiday unfolds over several days, beginning with preparations like building ofrendas and culminating in cemetery visits. On October 31 or November 1, angelitos are welcomed with toys and sweets, while November 2 focuses on adults. Iconic sites like Pátzcuaro in Michoacán host all-night vigils on Janitzio Island, with candlelit boats ferrying participants across Lake Pátzcuaro. Mexico City’s grand parade, inspired by cinematic depictions and first held in 2016, has become a major event, drawing millions and incorporating elaborate floats, music, and performances that blend tradition with modern spectacle.

Recent observances, such as those in 2025, have seen large-scale events with thousands of participants, featuring homages to cultural figures and commemorations of historical milestones like anniversaries of significant earthquakes or city foundings. These parades and vigils not only celebrate the dead but also address contemporary issues, such as resilience in the face of natural disasters, thereby evolving the holiday to reflect ongoing societal narratives.

Regional Variations

Regional differences enrich the holiday’s diversity. In Maya communities of the Yucatán Peninsula, Hanal Pixan involves preparing elaborate altars with mukbil pollo and other foods, emphasizing ancestral souls’ return. In Ocotepec, Morelos, visitors are offered tamales and atole at open-door homes, promoting a sense of communal sharing that extends beyond immediate family.

Beyond Mexico, Guatemala’s observances include flying barriletes gigantes, massive kites symbolizing messages to the heavens, and preparing fiambre, a cold salad of mixed meats and vegetables for family picnics at cemeteries. These variations reflect the holiday’s adaptation across Mesoamerican indigenous groups while maintaining core themes of remembrance. In other areas, such as Oaxaca, intricate face painting and costume contests add artistic flair, with participants embodying calacas to embody the blending of life and death in vivid, performative ways.

Observances in Other Countries

The Day of the Dead has spread globally through Mexican diaspora communities. In the United States, particularly in border states like Texas and California, adaptations from the 1970s integrated political themes, such as altars honoring victims of social injustices. Events like processions feature masks and urns for collective mourning, often incorporating elements of local culture to create hybrid celebrations that resonate with diverse populations.

In Guatemala, as noted, kites and fiambre dominate, while Ecuador’s indigenous Kichwa people consume colada morada, a purple fruit porridge, with guaguas de pan bread figures. Bolivia’s Día de las Ñatitas involves crowning family skulls with flowers and offerings like cigarettes. European countries like Italy observe similar customs on All Souls’ Day, with sweets like ossa dei morti cookies, and Asian nations like the Philippines blend Catholic rites with incense. These international adaptations highlight the holiday’s universal appeal, adapting to local contexts while preserving its essence of honoring the deceased through food, art, and community.

Modern Celebrations and Cultural Impact

Today, the Day of the Dead influences global culture, from educational programs to tourism. Community events foster inclusivity, with ofrendas in public spaces drawing large crowds and serving as platforms for cultural education. The holiday’s cultural impact extends to art, literature, and media, promoting themes of resilience and heritage. It challenges Western views of death, encouraging a celebratory approach that strengthens familial and communal ties, and has inspired initiatives in mental health and grief counseling by normalizing open discussions about loss.

Modern enhancements include technological integrations, such as virtual ofrendas for distant families or apps guiding participants through rituals, ensuring accessibility in an increasingly digital world. Tourism has boosted local economies, with guided tours and workshops offering immersive experiences, though efforts are made to balance commercialization with authentic preservation.

In Popular Culture

Popular culture has amplified the Day of the Dead’s visibility. Films vividly depict ofrendas, cempasúchil paths, and the journey to Mictlán, inspiring broader interest and even influencing real-world parades. Literary calaveras appear in schools and media, while Catrina imagery permeates tattoos, masks, and theater, such as classic plays. Dances like La Danza de los Viejitos in Michoacán add performative elements, blending tradition with contemporary expression. This cultural permeation extends to fashion, music, and literature, where motifs of calaveras and marigolds symbolize Mexican identity worldwide, fostering cross-cultural appreciation and creative reinterpretations.

Love never dies. It just wears flowers and finds its way home.

Hashtags For Social Media

#diadelosmuertos #dayofthedead #ofrenda #mexicanculture #lacatrina #calavera #sugarskull #marigolds #cempasuchil #papelpicado #pandelmuerto #mexicantradition #celebrationoflife #honoringancestors #mexico #mexicanart #culturalheritage #aztec #mayan #mole #tamales #vibrantmexico #fiestamexicana #ancestralroots #colorfultraditions #mexicofiesta #spiritualcelebration #diasdelosmuertosvibes #latinculture #unescoheritage

Related Questions, Words, Phrases

what is día de los muertos | when is day of the dead celebrated | what does the ofrenda represent | why do mexicans celebrate día de los muertos | how to make a día de los muertos altar | what foods are eaten on day of the dead | what do sugar skulls symbolize | what flowers are used for día de los muertos | how is day of the dead different from halloween | what is pan de muerto | how to decorate an ofrenda | what are traditional day of the dead symbols | where is día de los muertos celebrated | what is la catrina | what colors are used for día de los muertos | what are calaveras de azúcar | how do families honor ancestors on día de los muertos | what happens on november 1st and 2nd in mexico | how to celebrate día de los muertos at home | what are common día de los muertos traditions | how do you say day of the dead in spanish | what is hanal pixán | what does papel picado mean | why are marigolds important on día de los muertos | is día de los muertos a catholic holiday | what do the candles on the ofrenda mean | how do schools celebrate día de los muertos | what is written in literary calaveras | what is the history of día de los muertos | what do skeletons represent in mexican culture | what are the origins of día de los muertos | how is día de los muertos celebrated in guatemala | what is the significance of food in día de los muertos | how did aztec beliefs influence day of the dead | why is día de los muertos a unesco heritage tradition