At COP30 in Belém, Brazil (November 10–21, 2025), what was meant to be the most inclusive UN climate summit quickly sparked outrage over the treatment of Indigenous protesters. Delegates from groups like the Munduruku demanded faster land demarcation, rejection of destructive infrastructure, and real Free Prior and Informed Consent in climate decisions. Peaceful actions—blockades, sit-ins, and brief venue breaches—were met with heavy militarized police and National Guard deployments after the UNFCCC Executive Secretary urged stronger security. Critics say this created a chilling effect, sidelining land defenders while over 1,600 fossil-fuel lobbyists moved freely. The controversy highlights the gap between global climate goals and the rights of Amazon communities, raising serious questions about whose voices truly shape UN climate policy and whether future COPs will protect or suppress frontline defenders.

Long Version

COP30 Fallout: Accusations of UN-Backed Repression of Indigenous Rights at Amazon Climate Summit

The 30th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP30), held in Belém, Brazil, from November 10 to 21, 2025, was promoted as a landmark event that would place the Amazon rainforest and Indigenous peoples at the center of global climate action. Brazilian authorities described it as the most inclusive summit to date, with significantly higher Indigenous accreditation than previous conferences. Yet within days, the gathering descended into controversy over the treatment of Indigenous protesters, escalating security measures, and claims that UN leadership actively supported a heavy-handed response.

Roots of the Protests

Indigenous delegations arrived in Belém with clear demands: accelerated demarcation of ancestral territories, rejection of infrastructure projects that would deepen deforestation, revocation of plans to commercialize rivers, and an end to carbon-market schemes that bypass communities. Many highlighted ongoing invasions of their lands by loggers, miners, and agribusiness, as well as the continued killings of environmental defenders across the Amazon region.

Actions began peacefully but grew more disruptive as participants felt their concerns were being sidelined in formal negotiations. Demonstrators briefly entered restricted negotiation zones, staged sit-ins, formed human chains to block venue entrances, and organized river flotillas. Banners carried messages such as “Our land is not for sale” and called for full application of the principle of Free Prior and Informed Consent in all climate-related decisions affecting Indigenous territories.

A particularly symbolic moment occurred when Munduruku representatives maintained a 90-minute blockade of the main entrance to the negotiators’ area. The standoff ended only after direct dialogue with the COP presidency team, during which negotiators acknowledged the protesters’ grievances.

Security Escalation and the Role of UN Leadership

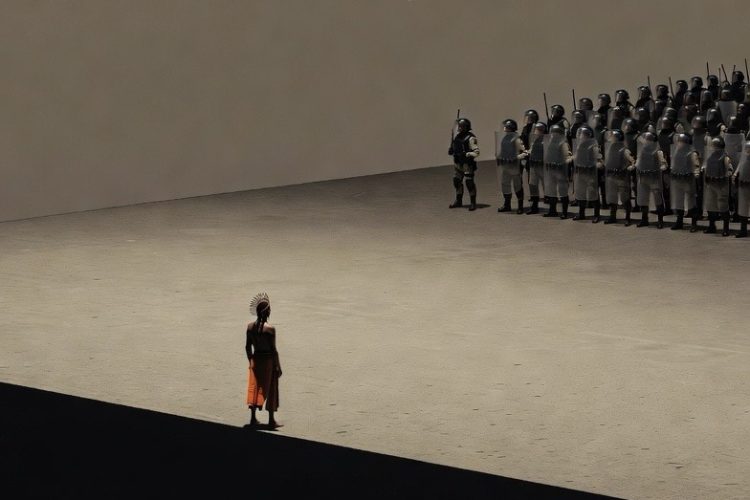

Following an early breach of restricted areas, the UNFCCC Executive Secretary sent a formal letter to Brazilian authorities describing the incident as a serious security failure and urging immediate strengthening of perimeter controls. Within hours, hundreds of riot police and National Guard troops in full tactical gear were deployed, establishing wide cordons around the venue and significantly limiting protest space.

Critics quickly pointed out the stark contrast: while Indigenous land defenders faced armed lines and restricted movement, more than 1,600 registered fossil-fuel industry representatives moved freely inside the summit. Over 200 human rights and environmental organizations condemned the response in an open letter, warning that requesting militarized intervention against peaceful Indigenous protesters set a dangerous precedent for future conferences and undermined the UNFCCC’s own human-rights commitments.

Broader Tensions Between Climate Goals and Rights

The events in Belém exposed long-standing friction between ambitious climate finance mechanisms and the rights of frontline communities. Proposals such as large-scale tropical forest funds and new carbon-credit systems were criticized for lacking meaningful Indigenous governance. Many delegates and observers noted that slowing deforestation and achieving a just transition cannot succeed without resolving land tenure conflicts and protecting those who defend the forest.

Despite earlier progress in reducing Amazon deforestation rates under the current Brazilian administration, Indigenous organizations argue that territorial demarcation remains critically delayed and that major infrastructure and extractive projects continue to advance.

Lasting Implications

As COP30 moves into its final days, the heavy security presence and accusations of repression have overshadowed substantive discussions on finance, mitigation targets, and adaptation support. The controversy has raised fundamental questions about whose voices truly shape global climate policy and whether the UNFCCC framework can accommodate legitimate dissent from the very communities most impacted by both climate change and many proposed solutions.

The outcome in Belém will likely influence not only immediate negotiation texts but also the perceived legitimacy of the entire UN climate process for years to come. For many Indigenous leaders and their allies, the events have reinforced a core message: protecting the Amazon and meeting global climate goals require upholding rights, not suppressing the defenders who have safeguarded the rainforest for generations.