Pediatric bipolar disorder (PBD) causes extreme mood swings, irritability, and mania in kids, often overlapping with ADHD or anxiety and resisting standard treatments. A key study in Frontiers in Child & Adolescent Psychiatry found 92% of 37 PBD children in a Lyme-endemic area had tick-borne infections like Lyme (Borrelia burgdorferi), Babesia, Bartonella, or Mycoplasma, with 59% showing multiple pathogens. These infections trigger brain inflammation, immune dysregulation, and symptoms mimicking PBD, especially in genetically vulnerable youth. Testing via ELISA, Western Blot, and FISH revealed hidden exposures; anti-inflammatory drugs like minocycline helped both infection and mood issues. Clinicians should screen for tick-borne diseases in treatment-resistant cases, particularly in endemic regions. Early detection and targeted antibiotics can improve outcomes, highlighting the need for interdisciplinary care in child mental health.

Long Version

Uncovering Hidden Triggers: The Link Between Tick-Borne Infections and Pediatric Bipolar Disorder

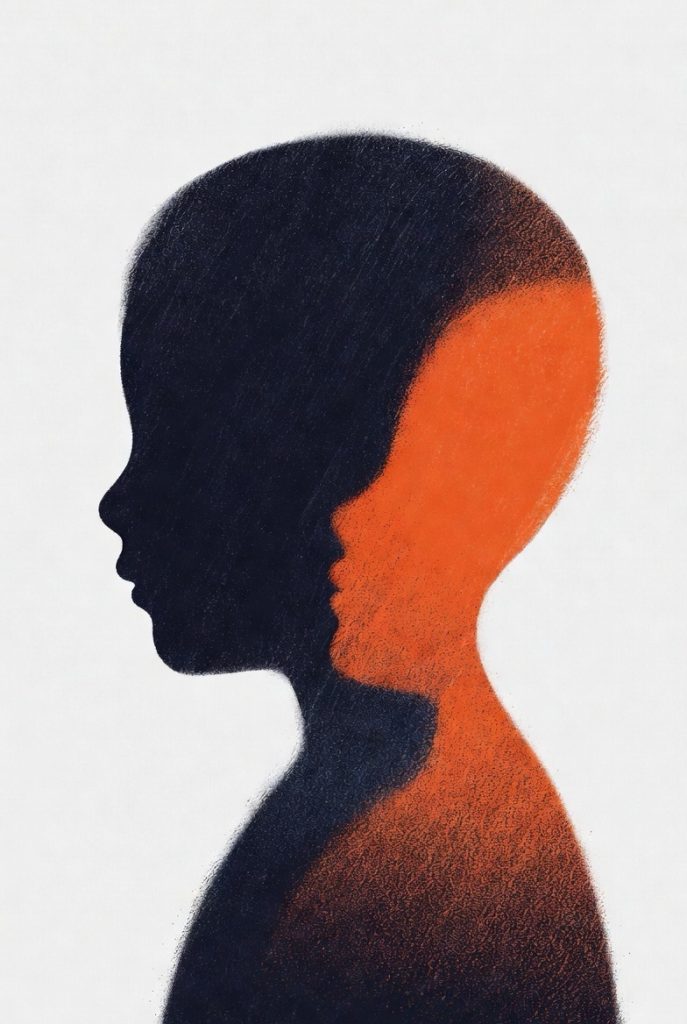

In the realm of child mental health, few conditions are as complex and debated as pediatric bipolar disorder (PBD). Characterized by extreme mood swings, irritability, and episodes of mania or depression, PBD affects a small but significant portion of youth, often leading to profound challenges in daily functioning, school performance, and family dynamics. Recent research has shed light on an unexpected environmental factor that may play a role in its onset or exacerbation: tick-borne infections (TBIs). A groundbreaking study published in Frontiers in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry revealed that 92% of children diagnosed with PBD in a Lyme-endemic region showed laboratory evidence of exposure to these infections, with many harboring multiple pathogens. This finding challenges traditional views in pediatric psychiatry and highlights the intricate interplay between infections, immune responses, and neuropsychiatric disorders.

Understanding Pediatric Bipolar Disorder

Pediatric bipolar disorder, also known as early-onset bipolar disorder, is a subset of mental disorders that manifests in children and adolescents, typically before the age of 18. Unlike adult bipolar disorder, PBD often presents with rapid cycling—frequent shifts between manic, hypomanic, and depressive states—along with chronic symptoms such as irritability, hyperactivity, and emotional dysregulation. According to diagnostic criteria from the DSM-5, it includes Bipolar I and II subtypes, with symptoms like elevated mood, decreased need for sleep, grandiosity, and in severe cases, psychotic features.

Prevalence estimates vary, but PBD is more commonly diagnosed in the United States than in Europe, with onset often occurring before age 13 in about a quarter of cases. This discrepancy may stem from gene-environment interactions, where genetic vulnerabilities meet external triggers. Adolescent psychiatry experts note that PBD can overlap with other conditions like ADHD, anxiety disorders, or obsessive-compulsive disorders, complicating diagnosis. Treatment-resistant disorders are common, with many youth experiencing persistent psychiatric symptoms despite standard interventions like mood stabilizers or psychotherapy. Factors such as family history of bipolar disorder, autoimmune disorders, or early-life stressors further influence its course, underscoring the multifactorial nature of this neuropsychiatric disorder.

The Role of Tick-Borne Diseases in Child Mental Health

Tick-borne diseases encompass a range of infections transmitted by ticks, primarily in endemic regions like the Northeastern United States. Common pathogens include Borrelia burgdorferi (the causative agent of Lyme disease), Babesia microti, Bartonella henselae, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Ehrlichia chaffeensis, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. These infections can lead to multisystem involvement, including somatic complaints like fatigue, joint pain, and neurological issues.

In children, TBIs often go unrecognized due to subtle or absent initial symptoms, such as a known tick bite—reported in only a minority of cases. Chronic infections may persist, crossing the blood-brain barrier and triggering neuroinflammatory triggers. This can result in immune dysregulation, elevated proinflammatory cytokines, and autoimmune processes, which disrupt neurotransmitter balance and contribute to mood disorders. Research from the psychoimmunology field indicates that these pathogens can induce inflammation in the central nervous system, mimicking or exacerbating psychiatric symptoms. For instance, Lyme disease has been linked to cognitive deficits, depression, and suicidal ideation in youth, with early contraction increasing long-term risks.

Key Findings from the Landmark Study

The study, a retrospective chart review of 37 youth diagnosed with PBD from a private practice in New Jersey—a state with high rates of Lyme disease and babesiosis—provides compelling evidence of this connection. Participants, with a mean age of 7.9 years and a male predominance (73%), underwent serological testing for various pathogens as part of a comprehensive evaluation that included family history of mental disorders, autoimmune conditions, and developmental milestones.

Laboratory criteria involved assays like ELISA, Western Blot, IFA, and FISH for direct pathogen detection, conducted at reputable labs such as IGeneX and Galaxy Diagnostics. Results showed exposure in 92% (34/37) of cases: Babesia in 51%, Bartonella in 49%, Mycoplasma pneumoniae in 38%, Borrelia burgdorferi in 22%, and Group A Streptococcus in 19%. Notably, 59% had multiple infections, amplifying potential neuroinflammatory effects. Clinical criteria, assessed by specialists in infectious disease, immunology, and rheumatology, confirmed active TBIs in 81% (30/37), based on symptom patterns, physical exams, and treatment responses.

This case series builds on prior work, including a smaller cohort of 27 cases, and suggests infections as environmental triggers in genetically susceptible children. Overlaps with PBD include chronic symptoms, sleep dysfunction, cognitive impairments, and responsiveness to anti-inflammatory agents like minocycline, which has shown efficacy in both conditions.

Mechanisms Linking Infections to Neuropsychiatric Symptoms

The connection between TBIs and PBD likely involves immune response pathways. Pathogens like Borrelia burgdorferi and Bartonella can evade the immune system, leading to persistent inflammation and autoimmune mimicry. This disrupts monoamine neurotransmitters, heightens stress responses, and compromises the blood-brain barrier, allowing neurotoxic effects.

Related syndromes like Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS) and Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infections (PANDAS) illustrate similar dynamics, where streptococcal infections or other triggers cause abrupt psychiatric symptoms. In PANDAS, anti-streptolysin O and anti-DNAse B titers indicate immune activation, potentially comorbid with TBIs. Studies show that infections can precede or worsen mood disorders, with elevated cytokines affecting brain regions involved in emotion regulation.

Geographic factors matter: Lyme-endemic regions report higher PBD rates, possibly due to Borrelia burgdorferi’s potent inflammatory profile compared to European strains. A Danish study linked early Lyme exposure to increased suicide risk, reinforcing long-term neuropsychiatric impacts.

Implications for Diagnosis, Treatment, and Clinical Practice

These insights urge a paradigm shift in pediatric psychiatry. For youth with treatment-resistant PBD or atypical presentations, clinicians should consider TBIs, especially in endemic areas. Routine screening via serological testing and clinical evaluation could uncover hidden infections, potentially altering treatment trajectories.

Therapeutically, antibiotics targeting specific pathogens—combined with anti-inflammatory agents like celecoxib or omega-3 fatty acids—may address root causes. Minocycline, with its dual antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties, holds promise for managing both infections and mood symptoms. However, challenges in testing accuracy—due to immunosuppressive effects of pathogens—highlight the need for advanced diagnostics like direct culture or FISH.

Organizations like the Bay Area Lyme Foundation advocate for integrating infectious disease workups into psychiatric assessments.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

While provocative, the study has limitations: a small sample from one practice introduces referral bias, and the lack of a control group precludes causality claims. Variability in testing timing and clinician judgments adds uncertainty. Prospective studies with standardized protocols, larger cohorts, and psychiatric controls are essential to validate these associations.

Broader research should explore gene-environment interactions, longitudinal outcomes, and interventions in non-endemic regions. Addressing diagnostic controversies in PBD—such as overlaps with other disorders—will enhance clarity.

Prevention and Broader Awareness

Preventing TBIs involves tick avoidance, prompt removal, and vaccines where available. Educating families in high-risk areas about symptoms can facilitate early intervention, potentially mitigating neuropsychiatric sequelae. In child mental health, fostering interdisciplinary collaboration between psychiatrists, infectious disease specialists, and immunologists is key to holistic care.

Conclusion

The intersection of tick-borne infections and pediatric bipolar disorder represents a frontier in understanding neuropsychiatric disorders. By recognizing infections as potential neuroinflammatory triggers, we can refine diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, offering hope for better outcomes in affected youth. This research not only enriches adolescent psychiatry but also underscores the need for vigilance against environmental factors in mental health. As evidence accumulates, it paves the way for more integrated, effective strategies to combat these challenging conditions.